by Veronika Helfert

From late September to early October 1950, a series of wildcat strikes took place in Austria. To this day, it is one of the largest strike waves in the country after the Second World War: between 120,000 and 220,000 workers participated. The October Strikes – supported mainly by communist trade union officials and those of the VDU (Verband der Unabhängigen, the political representation of former national socialists) – have remained utmost politically controversial to this day. The main reason for this was that some of the officials of the Austrian Trade Union Federation (ÖGB) and press framed these events as an attempted putsch (either by the communist party or the soviet authorities) in the context of the Cold War.[1] This allegation is widely rejected by historians today.[2]

These wildcat strikes were triggered by the fourth “Wages and Prices Agreement” between the Austrian government and the so-called social partners, including the ÖGB.[3] This instrument has been used since 1947 to try to keep inflation in check. The workers went on strike against the will of the ÖGB and many of them faced consequences: trade unionists were expelled for disrespecting orders, the workers did not receive compensation for the strike days, many were laid off.

At the end of October, the communist Member of the Austrian Parliament, Franz Honner, inquired about the police violence against “striking workers and their wives carried away by the movement against the price gouging package” as he put it.[4] In his formulation of “striking workers and their wives” (streikende Arbeiter und ihre Frauen) lies the problem the researcher has to keep in mind: Honner talks about striking workers and the wives who supported them in their struggle.

This provokes questions: were the wives no workers? Did women workers not participate in the strikes and demonstrations? Where do we find striking women workers? The problem of these silences in records of the past is long known and discussed among feminist historians.[5] Labour historian Samita Sen discusses a similar problem for the Indian context and also problematizes the use of language: official records don’t mention women, very often they describe gatherings and protests as if only men were present.[6]

So, what can we learn about striking women workers looking into police records, and what is evasive? Indeed, researching with textual sources in German poses the difficulty of the language of the use of male (plural) forms for women and men, as the example of Honner showed. The police records kept in the Austrian State Archives show a consistent use of male forms like Arbeiter (workers). Women (Frauen) or women workers (Arbeiterinnen) are rarely mentioned explicitly. The German word Arbeiter in the sources remains ambiguous, as it could mean male workers only or male and female workers.

Police documents from 1950 rarely reveal whether there were women in the crowd. However, the writing practices of police officers also differ. Sometimes they do indicate when women workers were present. This may well have been done with the purpose of denigrating the strike, as the following example shows. The police reported from the spinning factory Walek in Wiener Neustadt, a city south of Vienna. The factory workers – mainly women – did not participate in the strike. On 5 October, hundreds of communist workers showed up to prevent the women workers from starting their shift by insulting them with vulgar and sexist slurs and threatening with violence.[7]

The picture painted by the police documents looks like militant actions have been undertaken mainly by men. Records show mainly men arrested for offenses such as assault, sabotage, building barricades, etc. Nevertheless, there are also a few women named in the protocols, like a young girl, an eighteen-year-old unskilled worker, who was arrested because of agitating in front of a vocational school.[8] The Styrian police accused some communist female functionaries – “kommunistische Frauenführerinnen” – to have threatened the residents of the mining town Mürzzuschlag with violence if they won’t participate in the country-wide demonstration on 5 October.[9]

So: what can we learn from police records? They give us a limited, but nevertheless interesting perspective on women’s activism in strike movements: we can identify individual activists arrested or searched by the police while handing out leaflets or trespassing. Sometimes we can learn about percentage of women participating in events, when the police is reporting this. What we can also learn – to a limited extent – is the age, the profession, the party affiliation, networks, the home and birth address of women. We can get an idea about the demographic aspects. Only very rarely do we learn about motives and political agendas of activists – their perspective is missing.

References

[1] Cf. among others: Jill Lewis, “Austria 1950: Strikes, ‘Putsch’ and their Political Context,” European History Quartely 30, no. 4 (2000): 533–552.

[2] Cf. Oktoberstreik: Die Realität hinter den Legenden über die Streikbewegung im Herbst 1950. Sanktionen gegen Streikende und ihre Rücknahme [October Strike: The Reality behind the Legends about the Strike Movement in Autumn 1950. Sanctions against Strikers and Their Withdrawal], ed. Peter Autengruber and Manfred Mugrauer, rev. and 2nd ed. (Vienna: ÖGB Verlag, 2017).

[3] The cooperation of the representatives of employers (Wirtschaftskammer and Industriellenvereinigung) and employees (Arbeiterkammer and Trade Unions) among themselves and with the government in Austria is called Social Partnership. It was introduced after the Second World War.

[4]Interpellation by Franz Honner and comrades to the Federal Minister of the Interior at the session of the National Council on 12 October 1950. ÖSTA, AdR, 131.575-2/50.

[5] Cf. June Purvis, “Using Primary Sources When Researching Women’s History from a Feminist Perspective,” Women’s History Review 1, no. 2 (1992) 273–306: 279.

[6] Cf. Samita Sen, “Gender and Class: Women in Indian Industry, 1890–1990,” Modern Asian Studies 42, no. 1 (January 2008) 75–116: 96.

[7] Memorandum. ÖSTA, AdR, 133.506-2/50.

[8] Vienna Police Directorate, “Punishment of Crimes Committed in Connection with the Demonstrations in Recent Days”, 26 October, 1950. ÖSTA, AdR, 132.011-2/50.

[9] “Situation report of the Security Directorate for Styria at 11:25 am”, 4 October 1950. ÖSTA, AdR, 134.948-2/50.

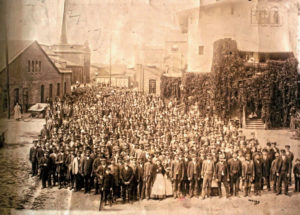

Illustration on top: Women Workers of a Factory of the Austria Federal Railway Company on strike in October 1950. The communist bimonthly Stimme der Frau is quoting one of the women describing their desperation with rising food prices. Stimme der Frau, 14 October 1950, 7.