by Veronika Helfert and Zhanna Popova

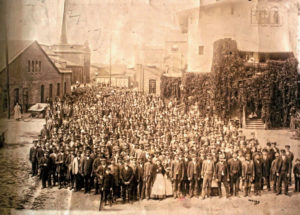

Picture: Szakszervezeti kirándulás / Trade union outing. Source: National Széchényi Library (OSZK) Budapest

Right from the start of her research, an historian investigating women’s labour activism is confronted with a challenge: sources often tend to focus on men rather than women, even when women were equally active during the described events. Official documents produced by state administration and (international) organisations, as well as press, often omit not only women’s perspectives, but sometimes their presence altogether. Other types of sources are not necessarily more inclusive. An example from the 1913 Dublin lockout illustrates this bias saliently. The lockout, which lasted almost five months and affected up to twenty thousand workers, was one of the most severe labour disputes in Irish history. It attracted international attention and support from foreign labour activists. Bill Hayworth, American socialist and activist of the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) trade union, visited Dublin during the lockout and was amazed to see what he thought was a familiar acronym – IWW – on banners all over the city. Only later was he told that it actually stood for Irish Women Workers – an organisation that women workers created in 1911 because other trade unions excluded them. The Irish Women Workers’ Union took an active role in the strike that preceded the lockout and fought to mobilise local and international public opinion to favour the striking workers.[1]

With this example, the exclusion of women workers from the mainstream labour movement becomes visible, as they were denied membership in other trade unions at the time. It also highlights a more subtle, hidden bias against women activists that often shaped the sources: even an involved observer automatically assumed that an all-women’s trade union was an entirely different, male-run organisation.

Historians studying women’s labour activism often must be resourceful and inventive when it comes to sources. Where official records can fail, poetry, songs, diaries, photos, oral history and even documents on household debt can help to better grasp activity of women as labour activists. These sources also show that the narrow definition of labour activism as limited to the workplace does not hold when confronted with the multiple tactics and strategies that women used to achieve their labour-related goals. Such sources underscore the importance of communal spaces and informal communication, organisation of childcare, consumer tactics as activism, and other understudied subjects.

Sources created by women workers in the most vulnerable positions – casual, precarious workers, those involved in “sweating industries” or poor rural labourers – are particularly scarce. Luckily, exceptions can be found. Women workers petitioned authorities to improve their situation. They talked to inspectors and investigators, and sometimes snippets of their accounts can be found in official reports. They also forged alliances with non-working-class women activists who participated in international feminist organisations. For instance, from 1908 on, Mrs. István Bordás, day wage rural labourer and an activist of the socialist peasant movement in Hungary, corresponded with Rosika Schwimmer, a journalist and internationally acclaimed Hungarian feminist. This correspondence also involved other peasant activists, and lasted for many years.[2] The letters tell the story of the fight for labour rights of poor peasant women in their own words.

The aim of ZARAH is to research women’s labour activism in Eastern Europe in its variety and complexity, and bring women activists that were often placed at the margins of labour, gender, and European history to the centre of historical inquiry. In the course of our study, we encounter precious sources that give a glimpse into the experiences of these women, experiences that were unknown, disregarded, or omitted before. The research agenda of ZARAH also includes making such sources available to the scholarly community and interested public via an online database. In order to showcase research in progress, we would like to share here some illuminating sources that we have encountered so far here, on the website of ZARAH. Sources such as these form the indispensable springboard for the thoughtful analysis of the history of women’s labor activism.

This series includes the following posts:

- Veronika Helfert discusses police records as sources on the 1950 strike wave in Austria.

- Ivelina Masheva analyses bulletins of a strike at a Bulgarian textile factory.

- Zhanna Popova investigates a factory photograph from the Kingdom of Poland.

- Alexandra Ghit examines a newspaper from a Romanian tobacco factory.

- Susan Zimmermann revisits materials of a large-scale research project on women workers in Hungary from the 1960s.

References:

[1] Moriarty, Theresa. “‘Who Will Look after the Kiddies’? Households and Collective Action during the Dublin Lockout”. In: Rebellious Families: Household Strategies and Collective Action in the Nineteenth and Twentieth Century, International Studies in Social History 3, edited by Jan Kok, 110–24. New York: Berghahn, 2002.

[2] Zimmermann, Susan, and Piroska Nagy (translation of source). “Female Agrarian Workers in Early Twentieth-Century Hungary.” Aspasia 12, no. 1 (January 1, 2018).