by Zhanna Popova

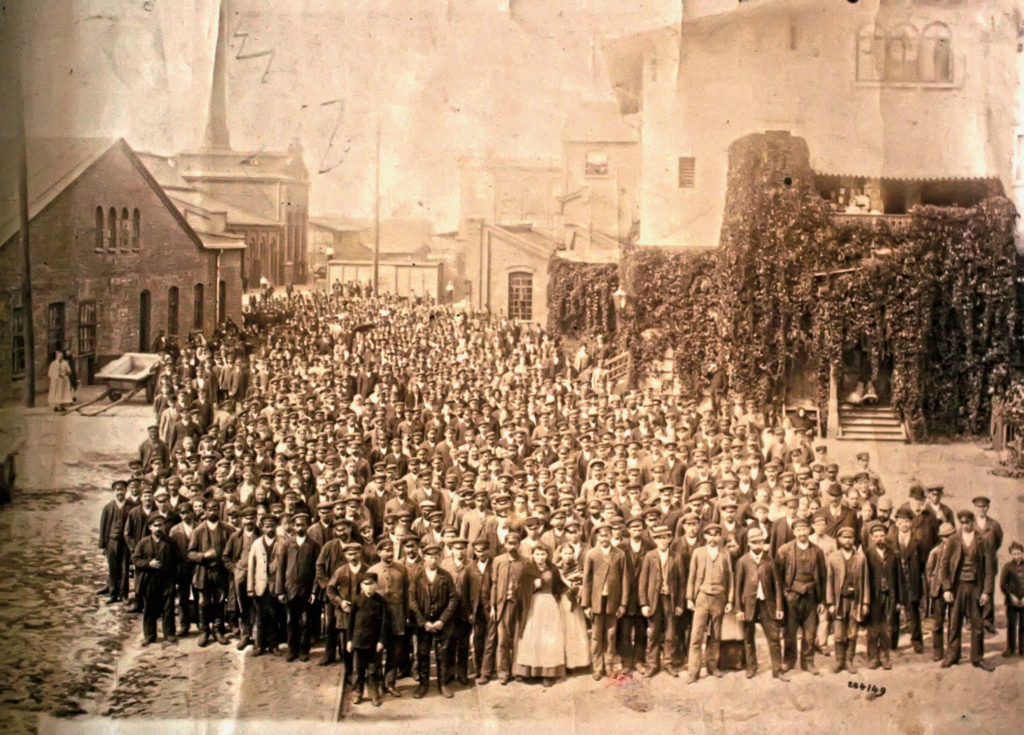

At first glance the picture featured in this blogpost seems easy to interpret. Against the backdrop of typical red-brick industrial buildings, workers of a large enterprise stand together in the factory yard, posing for a photograph, perhaps for the anniversary of the factory opening or some other occasion. Neat attire of workers and orderly composition of the shot suggest that this was an official photo.

There are several women and children pictured: most prominently, two women stand at the very front, one of them with a hand on the shoulder of the other. There are some more women here and there in the crowd. Basing on the photo alone, an observer could with certainty assume that the number of women working at this factory was vanishingly small.

This photograph, held in the collection of the Museum of Western Mazovia in Żyrardów, Poland (Muzeum Mazowsza Zachodniego w Żyrardowie), was taken some time in the second half of the nineteenth century and depicts the workers of the linen factory of Dittrich and Hielle. It also hides a mystery: where are the women workers?

Located between Warsaw and Łódź, the town of Żyrardów owed much of its economic development in the nineteenth century, and especially its explosive population growth, to the rapid rise of textile industry in the Kingdom of Poland.[1] A linen weaving factory was first installed in this town in 1830. In 1857, textile entrepreneurs Karl Dittrich and Karl Hielle, who already owned a textile factory in Bohemia, acquired the Żyrardów linen factory and set out to expand the production.

In the following decades, the Dittrich and Hielle factory indeed continuously increased its output and attracted ever growing groups of labourers from the surrounding villages and towns. By 1882, perhaps around the time the photo above was taken, 7,300 people were employed at the factory, including 2,500 women and approximately one thousand children.[2] In other words, at least one-third of all workers at the Dittrich and Hielle factory, contrary to what is conveyed by the picture, were women.

Why, then, were women absent in this official photo? It is, of course, impossible to give a certain answer, but a hypothesis can be offered. At the end of the nineteenth century, the figure of factory woman was a subject of discussions in press and literary works. Factory work was often considered a threat to what was proclaimed to be the main role of women in Polish society: motherhood. Long hours, unsanitary working conditions, heavy physical labour and insalubrious living quarters all contributed to the image of working women as unfit mothers. Perhaps it was this stigma against factory women that led them to be excluded: as this photo was destined to be a public representation of the factory, it is possible that the owners or the management featured male workers more prominently in order to create an appearance of a modern, healthy and morally fit workforce.

However, even as they were made invisible, the women workers of the Dittrich and Hielle factory managed to speak up and act in their own name. Indeed, in 1883 these women organised the first modern strike in the history of the Kingdom of Poland.

In the early 1880s, textile production in the Kingdom of Poland was affected by a crisis that had started in France and spread to other regions of Europe dominated by the textile industry. In case of Żyrardów, the factory management’s attempts to mitigate the crisis by lowering wages were first directed against the bobbin fillers (szpularki). These were low-paid workers, overwhelmingly women, whose task consisted in winding threads on bobbins for the weaving looms. There were approximately five hundred bobbin fillers at the factory, and all of them faced a cut of around one fourth of their daily wages.

Women workers reacted to the announcement of the cut calmly, but over the weekend, they coordinated a work stoppage to protest the wage cut.[3] On Monday 23 April 1883, the Żyrardów strike started when half of all bobbin fillers at the factory did not show up for work. The second half joined them in the following days. During the first days of the strike, the factory manager declined to address the striking women directly, but instead put pressure on their fathers and husbands, claiming that they would be fired unless women came back to work. Women, in other words, were not perceived as responsible for their own actions and not able to negotiate, but instead were to be called to order by their husbands and fathers. On 25 April, gendarmes arrived from Warsaw. Ten workers whom police identified as the initiators of the strike were arrested. Curiously, all of them were men.[4]

By Thursday, the whole factory stopped: due to the workflow of textile production, weavers (who were mostly male) could not run weaving looms without the constant supply of full bobbins. A large crowd assembled in town. Army was brought into the town on the same afternoon. Soldiers shot at unarmed workers, injuring and killing several teenage weavers, boys and girls. Despite the soldiers’ attack, the workers did not return to work, and on the following day their demands were satisfied. These demands were not limited to preserving the pre-cut salary for the bobbin fillers, but also included reduction of the working day by one hour for all workers, creation of factory stores that would have lower prices than elsewhere, financial support for those injured during the strike and paid funerals for those killed. Moreover, the workers were to be paid for the days of the strike. On 28 April, production at the factory was resumed.[5]

Triggers of this strike and the way it unfolded highlight the position of women labour activists in the textile industry: women were overrepresented in low-skilled, low-paid jobs at the factory and were the first to bear the brunt of an economic crisis. Their capacity for self-organisation, as the reactions of the factory management described above show, was not only questioned, but indeed unacknowledged. Yet in Żyrardów, women workers were ready to organise in order to counter the salary cut despite little initial support of male colleagues and without any example of earlier organised strikes, and were able to convey and defend their demands even though the managers of the factory initially refused to accept them as independent actors.

Although photographs create a powerful illusion of straightforward reflection of reality, the example discussed here shows that they need to be analysed in context and criticised as any other historical source.

References

[1] Between the end of the eighteenth century and 1918, Polish lands were partitioned between the Habsburg monarchy, the Romanov empire, and the Kingdom of Prussia. The Russian partition was referred to as the Kingdom of Poland, Congress Poland, or, later, the Vistula Land.

[2] Norman M. Naimark, The History of the “Proletariat”: The Emergence of Marxism in the Kingdom of Poland, 1870-1887 (Boulder, CO: East European Quarterly, 1979), 19.

[3] Z pola walki. Zbiór materyałów tyczacych sie polskiego ruchu socyalistycznego [From the battleground. Collection of materials pertaining to the Polish socialist movement] (London: Wydawnictwo Polskiej Partyi Socyalistycznej, 1904), 125.

[4] Alicja Urbanik-Kopeć, Anioł w Domu, Mrówka w Fabryce [Angel at home, ant at the factory] (Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Krytyki Politycznej, 2018, e-book edition).

[5] Z pola walki, 126-128.

Illustration: collection of the Museum of Western Mazovia in Żyrardów, Poland (Muzeum Mazowsza Zachodniego w Żyrardowie)