by Ivelina Masheva

Studying women labour activism requires the researcher to employ a wide variety of sources. Each of them sheds a different light, elucidating some aspects of working women’s struggle for better living and labour conditions, while at the same time leaving many blank spots and unanswered questions. Following the previous blogpost on strengths and weaknesses of police records as sources for research on women’ labour activism, I would now like to present another type of document – the strike bulletin and what it could reveal about women’s participation in the course of a particular strike.

At the end of June 1931, 800 predominantly women workers in the Tundzha textile factory in Yambol (Bulgaria) went on strike. Like many others during the Great Depression, this conflict was triggered by the employers’ attempt to optimize production costs. The Tundzha strike also had a long list of additional causes as the factory had been notorious for its unhygienic and unhealthy working conditions. In his memoirs, a former worker in the factory remembers that during the summer the temperature in the factory was 38°C, the air was extremely dusty and 40% of the workers had tuberculosis. The conditions were so bad that in the local paper a doctor compared the factory to a “tomb situated in the best part of town”.[1]

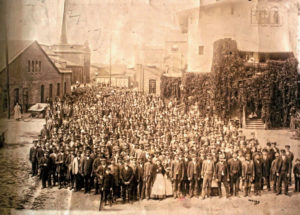

The dramatic nature of the conflict with its many violent collisions between the strikers and the police was widely covered by the press. Contemporary attitudes were divided along political lines with left-wing press emphasizing the rightfulness of strikers’ demands and condemning the disproportionate use of police force, while conservatives pointed out the involvement of communist trade unions and their ties to the Soviet Union to justify the repression. By contrast, during the state socialism period this event was incorporated into the party’s official narrative and its places of memory as evidenced by the photo above showing the monument of the striking textile workers.[2]

Twenty-one strike bulletins, published daily between 30 June and 20 July 1931, are a rich source on the course of the strike.[3] Information contained in these bulletins reflects their triple purpose. Primarily, their role was to inform the strikers about the development of the conflict. Thus, the first bulletin gave updates on the result of the ongoing negotiations – the workers’ demands which were met like improved working conditions and replacing some piece work remunerations with fixed wages, but also on the still unfulfilled demand of 20-30% wage increase. Another bulletin, published on 3 July 1931 gave an account of confrontations with the police, the number of injured and arrested activists and the state of the picket lines. Secondly, strike bulletins aimed to mobilize workers and to reinforce their sense of commitment to the cause. They included motivational texts and slogans, as well as calls for workers to stay firm against the repression, to unionize and to keep fighting for labour and social rights. Lastly, strike bulletins were also a tool for maintaining strikers’ unity, morale and discipline. They shared tales of solidarity and praised donations given to the strike fund, but also publicly shamed and ostracized strike breakers. The following excerpt gives а taste of the strike leadership’s rhetoric:

“One of the masters, Rashev, spent the whole night driving around the streets of the neighborhoods trying to persuade male and female workers[4] to go to work, deceiving them with various promises. But wherever he went, he got what he deserved: he was rejected everywhere and told “Your wife should go to work.” That’s what this sucker of workers’ blood deserve.

Male and female comrades!

Victory is close. But if we want an end soon – we must prepare for long labour! No dropping out! No bending! We are an iron race – the proletarian class! We know how to work, we can fight – we must win!”[5]

Although containing abundant and variegated information, the bulletins are insufficient for reconstructing the whole course of the strike as they end abruptly after 20 July 1931 following the mass arrests of the strike’s leading activists. They do not contain information on the final escalation of the police’s repression of the strike: on 22 July 1931, police shot at a workers’ assembly, killing two strikers. Wanting to end the strike as soon as possible, factory owners proposed wage increases ranging between 8 and 17% for different categories of workers, elimination of the piece work, provision of cloth for one outfit a year per worker and promised to improve working conditions. A new strike committee elected after the arrest of the previous one accepted the terms, and on 24 July 1931 the strike ended.[6]

The strike bulletins give a wide range of information on striking women’s tactics and strategies, their aims and goals, as well as their relationship vis-à-vis power brokers and authority figures such as the factory management, the police and the state in general. However, they also have their limitations. Like many documents on labour activism, these bulletins privileged the role of strike leaders and trade union officials (predominantly men) over rank and file strikers and non-unionized activists (predominantly women).

References

[1] Georgi Panchev, Mladost nasha [Our Youth] (Sofia: Narodna mladezh, 1972), 48.

[2] Pierre Nora, Les lieux de mémoire. (Paris: Gallimard, 1984).

[3] Op. 1, a.e. 195, f. 38B, Tsentralen Durzhaven Archiv [Central State Archive], Sofia, Bulgaria.

[4] Bulgarian language has gender distinct variations of some words like the German Arbeiter/Arbeiterin. Trade union and strike documents from this period, especially those addressing a predominantly female workforce, usually make an explicit reference to women workers.

[5] Bulletin 14, 13 July 1931, Op. 1, a.e. 195, f. 38B, Tsentralen Durzhaven Archiv [Central State Archive], Sofia, Bulgaria.

[6] Vasil Vasilev, Mariia Chervendineva, Mariia Ereliiska, and Petur Tsanev, Tekstiltsi: Organizatsiia i borbi na tekstilnite rabotnitsi v Bulgariia 1878-1944 [Textile workers: Organization and struggles of the textile workers in Bulgaria 1878-1944] (Sofia: Profizdat, 1970), 234-238.

Illustration on top: Yambol Strikers Monument. Foto: Lamiyta_Spaska, wikimapia.org.