by Ivana Mihaela Žimbrek

The main problem of urban households is relieving the working woman’s burden. Whenever we have analyzed women’s social engagement, the basic objective hindrance to their further development was the burden of household work, which drags them back into the house, and doesn’t allow them to be more actively socially engaged. How can we ask a woman worker, who has no one to help her in running the household, to be socially and politically active, when in addition to 8 hours of work, she spends on average 1-2 hours traveling from the factory or enterprise, and then another 8-10 hours on household work? How can we speak of professional or cultural development when she, as a mother and homemaker, spends her Sundays, vacations, and holidays cleaning, mending, and sewing? It’s no wonder that some women refuse to take on social and state functions and aspire to leave their jobs if their financial circumstances allow.[1]

Household work as the Yugoslav woman’s burden, described above by activist Branka Savić at the 1952 plenum of the Antifašistički front žena – AFŽ [Antifascist Women’s Front], was one of the main concerns of Yugoslav women’s organizations in the 1950s and 1960s. As rapid industrialization and urbanization enabled women’s increasing entrance into wage labor, the hours they continued to dedicate to household work were seen as the main obstacles to their social and political engagement.[2] In turn, modernization of household work was envisioned to improve women’s public engagement, increase their living standard, and modernize the home and the family where—as the organizations believed—the traditional, non-socialist way of life was proving difficult to change. These improvements were important to strengthen women’s emancipation and the general awareness of their new, equal status in the Yugoslav society.[3] As one of the leading Yugoslav communists Vida Tomšič wrote, the status of women was not simply a matter of legislation. Rather, it was one of the social processes in which women’s participation in the economic life of the country was the most important right.[4] This blog post outlines the Yugoslav women’s organizations’ various efforts in modernizing household work and shows in more detail some of the main preoccupations and initiatives in improving the conditions of Yugoslav women in the 1950s and 1960s.

The issue of women’s “double burden” in the field of paid work and unpaid household work was recognized immediately after the Second World War, as AFŽ was concerned that women’s progressive socio-economic and political role in “building socialism” was burdened by their regressive role in the domestic sphere.[5] To tackle this problem, AFŽ organized grassroots homemaking courses (the first ones for Partisan troupes) and engaged in improving domestic technology, activities which were part and parcel of their massive war and postwar efforts.[6] During the war, AFŽ provided help in the National Liberation Struggle in medical and care work, supply and material support, political and cultural education, and in battle, while in the aftermath of the war, the organization was active in the reconstruction of industry, retail, trade, transport, agriculture, social and educational institutions.[7] In the light of the economic, social and administrative changes in Yugoslavia from the late 1940s, marked by the self-management system, decentralization, and economic liberalization, AFŽ’s successors—the Savez ženskih društava Jugoslavije – SŽDJ, 1953-61 [League of Women’s Associations of Yugoslavia] and the Konferencija za društvenu aktivnost žena Jugoslavije – KDAŽJ, 1961-90 [Conference for the Social Activities of Yugoslav Women]—continued the organizational focus on the modernization of household work, education, healthcare, and maternity protection.[8]

From the 1950s, Yugoslav women’s organizations also insisted that “the social-political status of women is a social question that requires them [Yugoslav organizations] to change their relationship and praxis towards this problem.”[9] The solution for the “double burden”, therefore, had to be found in the self-managed Yugoslav society. As Branka Savić explained in her speech, “real women’s equality is possible only under the condition that childcare becomes social care, and that the household develops into social industry and gains a clear social function.”[10] Stemming from the understanding that modernization of household work should be based on its socialization combined with technological development, Yugoslav women’s organizations throughout the decade founded and promoted numerous institutions and initiatives for modernizing households and household work. The main scientific framework for their activities was home economics, a discipline that under Taylorist influence promoted the ideal of rational and efficient households.

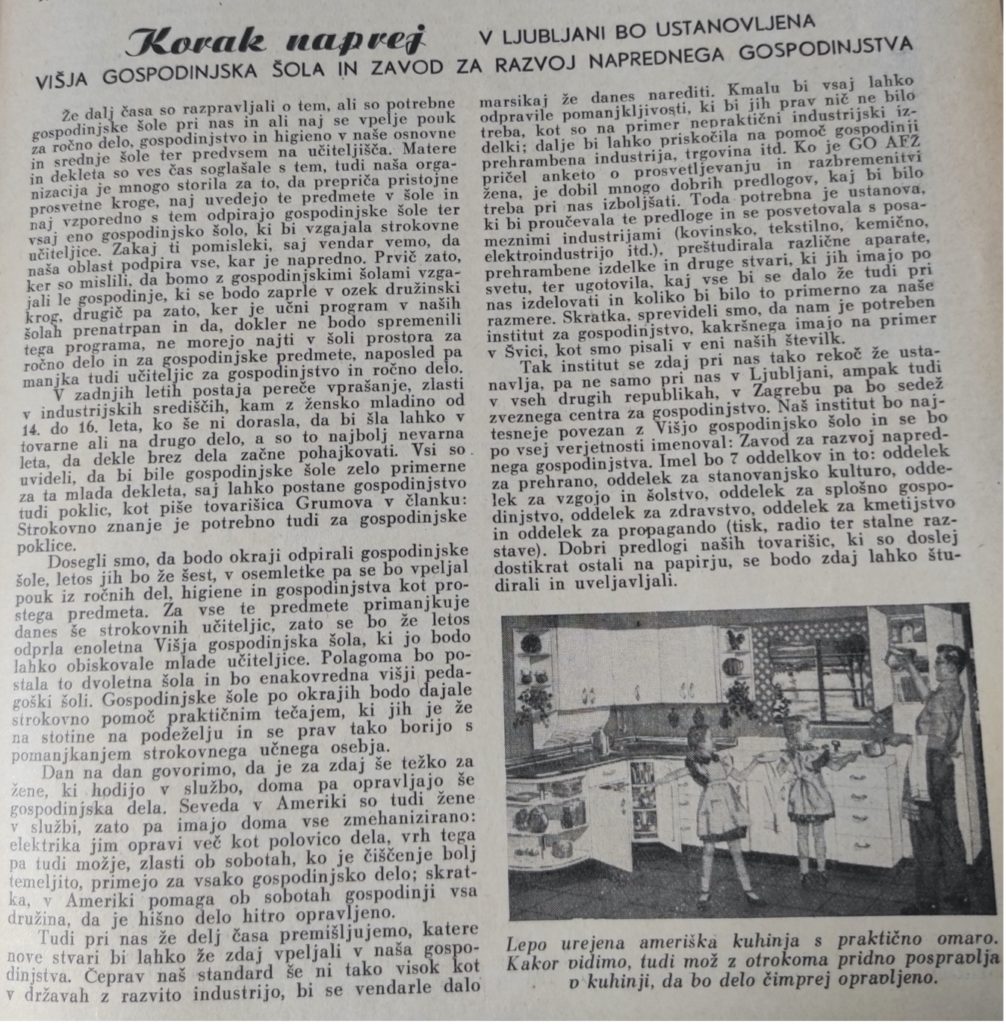

Home economics underpinned the organizations’ “educational work” through the institutionalization of domestic courses, which became subjects in schools, enterprises, workers’ and people’s universities, as well as in home economics schools, like the first Higher School for Home Economics in 1952 in Groblje (Slovenia).[11] Another important institution was the network of Centers for Household Improvement, which were interdisciplinary expert hubs focusing on topics like labour organization and technology in households, social nutrition, communal and commercial services in urban and rural areas, subsistence farming, education and childcare, architectural and urban design, textile and food industries.[12] From the first center in Ljubljana in 1954 to 124 centers in 1960, these institutions initiated domestic courses for the general public, roundtables, design competitions, exhibitions, national and international seminars, transnational exchanges, publications, and media efforts.[13]

In the 1950s and 1960s, similar concerns with household work were on the agenda of other Eastern and Western European organizations and institutions, such as Poland, East Germany, the Soviet Union, West Germany, and Scandinavia.[14] For Yugoslav women’s organizations transnational exchange was particularly relevant; during the 1950s, for example, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations financially supported both education in home economics institutions in Western European countries and the United States for members of women’s organizations and center employees, and visits from Western experts to Yugoslavia.[15] Simultaneously, Yugoslav women’s organizations exchanged ideas and experiences with other state-socialist organizations, most actively with their Polish counterpart Liga kobiet. Through mutual visits, seminars, and press exchange, Yugoslav women experts helped Liga kobiet establish their own Committees for Home Economics in the mid-1950s.[16]

Yugoslav women’s organizations’ most ambitious and popular initiative was probably a series of exhibitions at the Zagreb Fair, accompanying events and publications from 1957 to 1960 entitled “Family and Household.” Organized in collaboration with the Trade Union Federation of Yugoslavia, and supported by numerous other organizations and enterprises, the exhibition series showcased the plans and achievements in modernizing urban and rural households through appliances and technology, communal and commercial services, educational and welfare facilities, home design, consumer goods, and the self-management system.[17] The exhibited goods—produced or imported by Yugoslav and international enterprises—were assembled together to form model spaces, such as kitchens, stores, laundromats, or kindergartens. The use of various goods and spaces was demonstrated by instructors to millions of visitors, most of whom had encountered them for the first time, and were after the exhibition sent to Yugoslav republics.[18]

This brief overview shows Yugoslav women’s organizations’ multifaceted efforts in modernizing household through professionalization and institutionalization of expertise, general and specialized education, and popularization in the public sphere. As both experts and activists in home economics, Yugoslav women produced knowledge, raised public awareness, and emphasized interdisciplinary collaboration on a variety of topics, from housing culture, nutrition, and food technology, to educational and children’s institutions, women’s health, services, and modern retail. In contrast to the argument that women’s organizing in Yugoslavia lost its autonomy and progressive dimension after the dissolution of AFŽ, revealing the activism and expertise involved in the modernization of household work through home economics highlights new emancipatory agendas and the vibrant landscape of Yugoslav women’s activism in the first postwar decades.[19]

References:

[1] Branka Savić, “Osnovni problem domaćinstva: vaspitanje i rasterećenje radne žene,” [“Basic Problem of the Household: Education and Relief for the Working Woman”], Žena danas, no. 103, 1953.

[2] Vida Tomšič, Žena u razvoju samoupravne socijalističke Jugoslavije [Woman in the Development of Self- managed Socialist Yugoslavia]. Beograd: Jugoslavenska stvarnost, 1981, 90.

[3] Neda Božinović, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku [The Woman Question in Serbia in the 19th and 20th Century]. Beograd: Devedesetčetvrta, 1996, 177.

[4] Vida Tomšič, “Postoji li kod nas žensko pitanje?” [“Is there the Woman Question?”], Žena u borbi, no. 3, 1952.

[5] “Kakova je perspektiva za žene u daljnjoj izgradnji socijalizma,” [“What is the Perspective for Women in the Further Building of Socialism”], Žena u borbi, no. 10, 1952.

[6] Duša Švajger, “Začetki gospodinjskega izobraževanja v partizanih,” [“The Beginnings of Household Education in the Partisans”], Sodobno gospodinjstvo, no. 16-17, 1955; Anka Bujas, “Domaćinsko obrazovanje u školama i tečajevima,” [“Domestic Education in Schools and Courses”], Žena u borbi, no. 3, 1953.

[7] Neda Božinović, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku [The Woman Question in Serbia in the 19th and 20th Century]. Beograd: Devedesetčetvrta, 1996, 149.

[8] I use the plural expression “Yugoslav women’s organizations” to signify in the organizational transformations in the 1950s and 1960s and the organization’s decentralized character. With the introduction of the self-management system and decentralization of the Yugoslav state, AFŽ was transformed in the early 1950s into the decentralized SŽDJ and later KDAŽJ, whose common agendas were differently pursued by branches on county, city, and republic levels. In the case of modernization of household work, I believe the most active were the Slovenian and Croatian branches. For insights into historiography on Yugoslav women’s organizing, see Chiara Bonfiglioli, “Women’s Political and Social Activism in the Early Cold War Era: The Case of Yugoslavia,” Aspasia 8, no. 1 (January 1, 2014).

[9] Neda Božinović, Žensko pitanje u Srbiji u XIX i XX veku [The Woman Question in Serbia in the 19th and 20th Century]. Beograd: Devedesetčetvrta, 1996, 177.

[10] Branka Savić, “Osnovni problem domaćinstva: vaspitanje i rasterećenje radne žene,” [“Basic Problem of the Household: Education and Relief for the Working Woman”], Žena danas, no. 103, 1953.

[11] Archives of Yugoslavia, 354. Yugoslav Association of Women’s Societies, 7. Activities in the Society and Family; “Družina i gospodinjstvo 1960,” [“Family and Household 1960”], Sodobno gospodinjstvo, no. 5, 1960; Katedra “Porodica i domaćinstvo” na narodnim univerzitetima,” [“The Family and Household Department at People’s Universities”], Porodica i domaćinstvo, no.1-2, 1960.

[12] “Centri za unaprjeđenje domaćinstva,” [“Centers for Household Improvement”], Žena u borbi, no. 7, 1956.

[13] Emilija Šeparović, “Katedra “Porodica i domaćinstvo” – koordinator svih faktora za pomoć porodici,” [“The Family and Household Department – Coordinator of all Factors for Family Help”], Katedra “Porodica i domaćinstvo”, no. 5, 1960.

[14] See Basia Nowak, “‘Where Do You Think I Learned How to Style My Own Hair?’ Gender and Everyday Lives of Women Activists in Poland’s League of Women,” in Gender Politics and Everyday Life in State Socialist Eastern and Central Europe, ed. Shana Penn and Jill Massino, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009; Karin Zachmann, “A Socialist Consumption Junction: Debating the Mechanization of Housework in East Germany, 1956-1957,” Technology and Culture 43, no. 1 (2002); Susan E. Reid, “The Khrushchev Kitchen: Domesticating the Scientific-Technological Revolution,” Journal of Contemporary History 40, no. 2 (April 2005); Beška Frntić, “Domaćinsko prosvjećivanje u Danskoj,” [“Household Enlightenment in Denmark”], Žena u borbi, no. 5, 1956; Nada Marinković, “Utisci Pepce Kardelj po zemljama Skandinavije,” [“Pepca Kardelj’s Impressions of Scandinavia”], Žena, no. 8, 1959.

[15] Croatian State Archives, 1234. Conference for the Social Activity of Women, 13. Improvement of Households (1958-1960).

[16] “Predstavnice Lige poljskih žena u našoj zemlji,” [“Representatives of Liga kobiet in Our Country”], Žena danas, no. 143-144, 1956; E. Š. “Utisci s puta u Poljskoj,” [“Impressions from the Trip to Poland”], Žena u borbi, no. 11, 1956; L. Lubowska, “Seminarium polsko-jugosławiańske,” [“The Polish-Yugoslav Seminar”], Nasza praca, no. 8, 1961.

[17] Archives of Yugoslavia, 117, Association of Yugoslav Trade Unions, 236. Women’s Commission.

[18] State Archives Zagreb, 1172. Zagreb Fair, 2312. Propaganda and Additional Materials–1958.

[19] Lydia Sklevicky and Dunja Rihtman Auguštin, Konji, žene, ratovi [Horses, Women, Wars], Zagreb: Ženska infoteka, 1996, 82.

Illustrations:

- Article “A Step Forward: The Higher School for Home Economics and Center for Household Improvement Will be Established in Ljubljana”. Source: Naša žena, no. 11, 1952.

- Branka Savić and AFŽ members, VI Plenum of the AFŽ Central Committee, Sarajevo, December 1952. Source: Žena danas, no. 103, 1953.

- Alicja Musiałowa (middle), Angela Ocepek (center-right top) and members from Liga kobiet during their visit to Slovenia, June 1956. Source: Naša žena, no. 7-8, 1956.

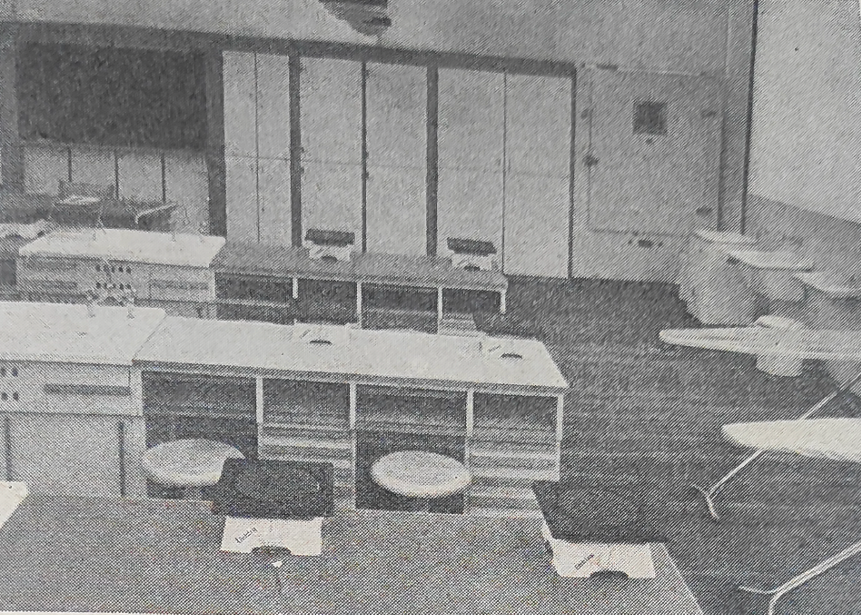

- Classroom for the home economics course designed for an elementary school in Ljubljana and displayed at the Family and Household exhibition in Zagreb, 1958. Source: Sodobno gospodinjstvo, no. 8-9, 1958.

Ivana Mihaela Žimbrek is a PhD candidate in History at Central European University in Vienna. She works on her dissertation on the history of department stores, modernization of retail and urban space in Socialist Yugoslavia.