by Doreen Blake

“Work” has had different meanings in time and within different milieus. As it will be shown in this blog post, between 1918 and 1934, in Austria, the general view in Catholic circles was that there were specific kinds of work women were supposed to be responsible for in the economic, domestic, and spiritual spheres, on account of a presumed female nature. In the Catholic women’s press of the 1920s and the 1930s, discussions on work and recommendable professions for women were influenced by considerations of class and marital status (whether women were married or unmarried).

The Catholic Church – an institution dominating Austria’s political and cultural life and social discourse – viewed women’s primary responsibilities as tied to motherhood, care, and the spread of Christian values. In other words, in the Catholic milieu, Arbeit [work] sometimes took on a different sense and transcended the meaning of gainful employment. Contemporaries often talked about women’s work or Catholic women’s work but meant by that the fulfillment of the Christian duty – carrying the Christian worldview into society and living a righteous, humble, Christian life for the spiritual and moral benefit of the family. Women were considered to be more religious than men and blessed with a serving and devoted nature, and that is why these responsibilities were assigned to them. Gainful employment was not meant to play a big role in Catholic women’s lives.

In Austria, the first Catholic women’s associations were founded after the revolution of 1848. Their (voluntary) work consisted mostly of charitable activities. At the beginning of the twentieth century, Katholische Frauenorganisationen [Catholic Women’s Organizations] (KFOs) were created in every federal state of Austria.[1] At the beginning of the 1930s, the eight KFOs had about 190 000 members.[2] Their purposes encompassed public welfare, religious education of their members and the members’ families, spreading the Christian worldview, and the fight against the presumed decline of moral standards. Also, the Catholic Church found it necessary to fight Social Democratic and other liberal ideologies in an organized way. The umbrella organization Katholische Reichsfrauenorganisation [National Catholic Women’s Organization] (KRFO), founded in 1907, was meant to serve as a bulwark against a perceived increase of immorality and a decrease in Catholic belief.[3] Also, the KRFO was supposed to take care of the moral and religious education of the female youth, for the benefit of the family which was considered the foundation of society.[4]

In the interwar period, Catholic Women’s Organizations (KFOs) focused on disseminating information through print media which could reach even remote areas in rural Austria. From 1918 to 1938, the KFOs published around twenty magazines. These magazines were used to shape opinions, convey core values and make known the Catholic worldview to a female readership.

After World War I, women’s employment was discussed widely within the KFOs’ press. Journals expressed surprise about “the performance of female work in formerly male professions”,[5] meaning the quality of the work done by women. Yet despite the surprising quality, it was suggested that women’s work was not supposed to “continue to exist in times of peace to the same extent as during the war”.[6] The quoted statement, by the Statistical Office in Germany, was re-printed in Österreichische Frauenwelt [Austrian Women’s World], the journal of the KRFO.

Throughout the interwar period, the KFOs’ fundamental attitude towards women’s gainful employment was ambivalent. Members of the organization supported (married) women’s decision to work if there was an existential need for them to earn money. Simultaneously, in the journal Frauen-Briefe [Women’s Letters][7], it was argued that the “permanent gainful employment of the married woman and mother was opposed to the welfare of the family”.[8] In fact, if one looks for articles about employment in the journal Frauen-Briefe there is not much to find. Außerhäusliche Erwerbsarbeit [out-of-house employment] is mentioned in only five issues.

The KFO’s position on female employment became more clearly articulated especially in the course of the introduction of the Doppelverdienerverordnung [Double Income Regulation]. The Double Income Regulation was introduced in 1933 by the federal government. It barred wives of men in the civil service from working, respectively it mandated women’s dismissal from the civil service if their husbands were earning too much. The aim was to limit women’s professional activities, benefit families and children, and fight rising unemployment among men – the Regulation combated the employment of both spouses and other persons living in one household.

In 1931, two years before the Double Income Regulation, the basic stance of the KFOs was that “the out-of-house employment of the married woman and mother was a social outrage”[9] and that women should only have the right to work in situations of economic hardship. Catholic women thought that the welfare of the family was in danger and that the double burden of the “homemaker”[10] was a problem. To ensure that the mother was able to fulfill her housewifely duties, (middle-class) families were supposed to rely on the secure income and support of the male head of the family, the Familienvater. But if this could not be guaranteed, gainful employment became very much the right and duty of married women, the magazine argued.

The stances of magazines such as Frauen-Briefe were different regarding unmarried women. Young girls who were not yet married were supposed to choose an education and a profession according to their alleged female nature, such as teachers, midwives, or welfare workers. They were supposed to pursue their profession only until they got married, except if they needed to continue to work due to financial reasons. The National Association of Christian Domestic Aids [Reichsverband der christlichen Hausgehilfinnen] wrote about the kind of work most suitable for young girls, domestic labour. Even though it was acknowledged that “personal service for people is very hard”[11] and “requires the greatest self-denial”[12], “serving and taking care of others is [nevertheless] women’s very own profession”[13]. This statement captures well the attitude the KFOs shared with the Association of the Christian Domestic Aids on the issue of women’s paid work outside the home – working was fine, but only before marriage and/or if it was an economic necessity, and only in professions that corresponded to the “female nature”.

However, what was suitable for young women depended on their class position: the KFOs often recommended middle/upper-class professions, while the Association of Christian Domestic Aids saw domestic work as suitable for working-class young women. Factory work was not considered appropriate for women, while agricultural work was. The KFOs had a high number of members in the countryside, therefore a lot of them served as farm maids, and farm workers or came from peasant families.

Despite the widespread belief that women should not practice a profession nor have employment outside of the house – unless they had to – there were quite a few associations explicitly for women workers, among others Verbände der christlich organisierten weiblichen Arbeiterschaft [Associations of the Christian Organized Women Workers].[14] These associations were in direct competition with social democratic associations and trade unions. Consequently, they were supposed to mobilize and organize working women and created a space for Catholic women workers to gather, engage in mutual help, and strengthen their Christian worldview.

All in all, women’s work was a very ambivalently discussed topic within the Catholic Women’s Organizations. It all depended on women’s marital status, if they lived in the countryside or the city, and which profession they chose. Individual development and different ways of living were not a top priority. Nevertheless, demands for free professional development existed, even in Catholic circles, but only within the limits given by the Catholic Church and only for members of the (urban) middle class. The analysis of the Catholic women’s press shows, that the position of members of the KFOs was shaped by Catholic beliefs on the one hand and pragmatism on the other hand.

References:

[1] For a list of the KFO foundations in Austria and further information see https://fraueninbewegung.onb.ac.at/organisationen/K (last access 28.11.2022).

[2] Cf. Fanny Starhemberg, Die katholische Frauenbewegung [The Catholic Women’s Movement]. In: Alois Hudal, ed., Der Katholizismus in Österreich [Catholicism in Austria]. Innsbruck, Wien, München: Verlagsanstalt Tyrolia, 1931, 305-318, 309.

[3] Cf. Michaela Kronthaler, ‚Die Frauenfrage als treibende Kraft. Hildegard Burjans innovative Rolle im Sozialkatholizismus und Politischen Katholizismus vom Ende der Monarchie bis zur „Selbstausschaltung“ des Parlaments‘ [The question of women’s rights as a driving force. Hildegard Burjan’s innovative role in Social Catholicism and Political Catholicism from the end of the Monarchy until the ‘Parliament’s self-cutoff’]. Graz, Wien, Köln: Verlag Styria, 1995, 35-40.

[4] Cf. Gabriella Hauch, „Arbeit, Recht und Sittlichkeit“. Die Frauenbewegung als politische Bewegung 1848 bis 1918 [“Work, right and morality“. Women’s movement as a political movement 1848-1938]. In: Gabriella Hauch, ed., Frauen bewegen Politik. Österreich 1848–1938. Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2009, 23–60, 33f.

[5] Hanny Brentano, Abbau der Frauenarbeit [Degradation of women’s work]. In: Österreichische Frauenwelt 4 (April 1918), 97-103, 103.

[6] Ibid., 103.

[7] Frauen-Briefe [Women’s Letters] was the journal of the KFO Vienna. From 1926 until 1938, Frauen-Briefe was published monthly, with a circulation of up to 45,000 copies. Its content was rather more political, compared to the content of other Catholic women’s journals. For example, Frauen Briefe included statements by Catholic Women’s Organizations on the issues of the day. Other Catholic women’s journals focused on topics “for women”, such as parenting, recipes, general tips on how to run a household or simple stories with a moral message.

[8] N.N., Denkschrift zum Entwurf eines Doppelverdienergesetzes [Memorandum on the concept of a double income law]. In: Frauen-Briefe 86 (February 1933), 3-4, 4.

[9] Angelina Schlösinger, Unsere Stellungnahme zum Doppelverdienergesetz [Our opinion on the double income law]. In: Frauen-Briefe 72 (December 1931), 3.

[10] Ibid., 3.

[11] N.N. Berufswahl [Choice of profession]. In Frauen-Briefe 80 (August 1932), 6.

[12] Ibid., 6.

[13] Ibid., 6.

[14] For more information see, for example: Michaela Kronthaler, Ambivalente politische Zielsetzungen der Katholischen Frauenbewegung Österreichs in der Zwischenkriegszeit [Ambivalent political objectives of the Austrian Catholic Women’s Movement in the interwar period]. In: Rudolf Zinnhobler u.a., eds.,Kirche in bewegter Zeit. Beiträge zur Geschichte der Kirche in der Zeit der Reformation und des 20. Jahrhunderts. Graz: styria medien service, 1994, 263-285, 273.

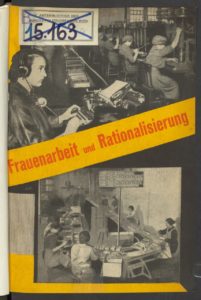

Illustration: Title of the 1933 November issue of Frauen-Briefe [Women’s Letters].

Doreen Blake studied History, Contemporary History and European Studies and is now a university assistant at the Department of History at the University of Vienna. She is currently finalizing her dissertation about the Catholic-female Agency of Catholic Women’s Organisations in the Context of Political Catholicism in Austria 1918-1934, supervised by Gabriella Hauch.