by Sára Bagdi

Little is known about the role of women agitators in labour activism of the 1900s Hungary. At the Újpest jute factory, Klára Balázs was the prime mover of local activism for several years. She worked closely with Lajos Kassák (1887-1967) who was one of the central figures of the Hungarian avant-garde. Kassák arrived from Érsekújvár (Nové Zámky, Slovakia) to the Hungarian capital in 1904 and worked as a skilled locksmith in several factories at the periphery of Budapest between 1904 and 1908. In his autobiographical novel, Egy ember élete (The Life of a Man), Kassák discusses his involvement in several factory strikes. The divergent socio-economic conditions from which these strike movements emerged allowed him to look at the practical, organizational problems of the strike actions from various angles. When he talks about the strike at Adolf Aigner’s factory, he introduces the readers to the bargaining process between the workers and the factory leadership. In the chapter dedicated to the time Kassák spent in the jute factory, the focus falls on the conflicts developed between the union bureaucracy and the women workers of the factory. The latter section not only provides us with some insight into the Social Democratic Party’s mismanaged attempts to reach out to women workers and engage them in union activism. It also makes visible the work of those little-known, socialist agitators who recognized these conflicts and sought to address them in a meaningful way. Kassák’s novel, despite his genuine attempts to question gender stereotypes, still carries implicit biases towards young women workers. Nevertheless, his recollection of Klára Balázs, a dedicated young socialist agitator, helps us to gain a better understanding of the challenges women workers were facing in the field of labour activism.[1]

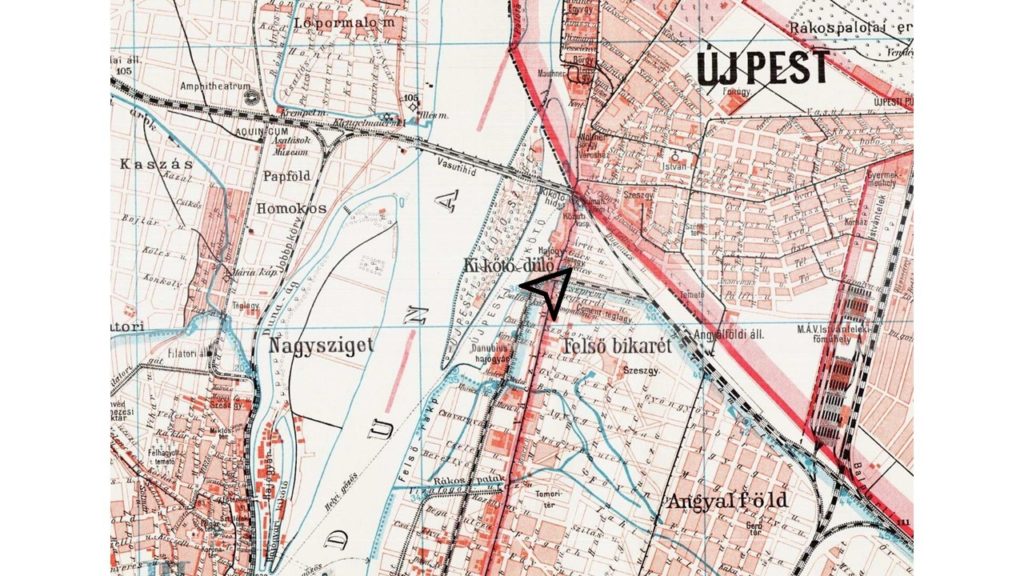

Kassák and Balázs first met in 1907 when he got hired at the Újpest jute factory. Kassák started working there after he had been unable to find any other job in high-profit sectors, as he was black-listed due to his previous involvement in factory strikes and labour union activism. By his own admission, Kassák went to the factory’s gatehouse “out of habit” and did not expect to get hired. The factory produced cheap jute bags for mills[2] in Újpest, one of the main industrial hinterlands of Budapest, which is today part of the city. Both the wages and the labour conditions were significantly inferior there compared to the Hungarian-Belgian Metal Goods Factory or the Budapest Road Railway Company, where Kassák had previously worked. The jute factory employed unskilled workers, mostly young women and adolescents, and only a small portion of its vulnerable labour force were involved in the high-risk trade union activism. Nevertheless, Kassák soon found a young socialist woman among them whom he could count on for political agitation. In Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Kassák recollects how his professional friendship and camaraderie started with Klára Balázs:

“During a midday break, I met a weaver, and in this girl I found a valuable socialist agitator. Her name was Klára Balázs, she was a member of the Újpest Workers’ House and the Anti-alcoholic Lodge. I had never met before such a serious and intelligent woman among the workers.”[3]

We know very little of Balázs; she was of working-class background and she might have been around the same age as Kassák who was 21 at that time. Her name appears in the strike reports of Népszava in 1907, thus we know that Balázs actively participated in at least one strike movement before she met Kassák.[4] Another worker from Újpest, Ferenc Szabó, also mentions in his recollection that Balázs played a major role in organizing the women’s community of Újpest, though he does not elaborate on what was her contribution.[5]

Kassák and Balázs worked closely together in organizing local labour activism for about a year. In May 1908, they succeeded in mobilizing the entire factory community in a strike for a 25% wage increase.[6] Kassák, in his novel, does not provide any substantial information on the pre-1908 history of the factory and describes the jute factory workers as unskilled women of peasant origin, who have never gained any firsthand experience with the wage struggles of the urbanized working class.[7] The 1908 strike, however, was not an isolated phenomenon. The history of the factory has been marked by regular wildcat strikes from the very beginning. These strikes broke out mainly for two reasons. Firstly, when there was an overproduction crisis, the factory management reduced workers’ wages in an attempt to compensate for the company’s loss.[8] Secondly, labour inspectorates regularly used physical abuse against young, female workers, and the violent harassment eventually resulted in resistance.[9]

Though the factory formally had a union since 1896, non-union-organized wildcat strikes remained prevalent. In 1903, after a major wildcat strike had failed, Népszava, the official journal of the Hungarian Social Democratic Party, concluded that this failure was going to strengthen the workers’ commitment towards the union.[10] Indeed, during the 1903 events, party representatives held regular speeches in favor of the union.[11] Nevertheless, four years later, when Kassák started working at the factory, according to his recollection, there was not any meaningful attempt of political agitation or serious organizational work on the part of the trade union and the social democrats: “No one even considered them worthy to approach them with the intention of organizing, and now we have realized that there were many thoughtful and progressive people among them.”[12]

In his autobiographical novel, when Kassák wants to give a sense of how jute factory workers were perceived among the skilled, male union workers, he writes: “Until now, we have taken these peasants for dumb, thick-headed coolies.”[13] Later in the text, Kassák disproves many of these stereotypes, but he does not mention the fact that union bureaucracy could offer little reason why these women would have an interest in joining the unions. Unions traditionally developed for representing skilled workers of high-profit sectors whose practical skills provided them with a stronger position in advocacy during wage strikes. The occupational segregation of women in low-paid jobs, like the textile industry, cemented them in unskilled or semi-skilled positions in an industrial sector where the agency of the unions, as well as the workers’ bargaining power, were almost non-existent.[14]

For all these reasons, Kassák and Balázs first approached the workers with seemingly minor, rather symbolic acts, for example, they organized a dance ball.

“I never dared to believe that we could achieve results so easily in the factory. These peasant people were still completely virgin soil for socialism, and since we approached them on an emotional rather than a scientific basis they were inclined to listen to us, they joined the union, and started showing up at the House (Újpest Workers’ House) in the evenings.”[15]

Kassák pays little attention to the socio-economic conditions in the factory, therefore his account leaves some room for the implication that these symbolic acts were effective because women workers were more receptive to emotional manipulation than economic reasoning. Symbolic acts succeeded over traditional, unionist tactics of economic agitation, first of all, because unions of the textile industry could not show any bargaining power against the factory leadership. Secondly, though the everyday conflicts between the trade union and the workers had practical, organizational, and economic reasons, in addition to the underlying organizational problems, a number of cultural and discursive practices excluded women from the workers’ movement. According to Kassák, mainly peasant girls came to the factory whose appearance and habitus were clearly distinct from the socio-cultural milieu of the urban working class. When Kassák labels these women as peasants, he makes it clear that from the perspective of union members, unskilled women workers were not even considered as working class or allies. Dance balls, where women of the jute factory and the wider working-class community of the neighborhood could meet informally, gained specific importance because otherwise skilled, male workers would not interact with these women, or as Kassák puts it: “the young apprentices, who would not have spoken to these ‘Panca Maris’ (sic!) in the street, slowly wandered into the hall, fell into the dance.”[16]

Kassák and Balázs, at Balázs’s suggestion, also organized a twice-weekly house court for the workers to provide them a forum “where personal conflicts between workers could be settled peacefully.”[17] These events also became an effective forum for agitation as they provided Kassák and Balázs an opportunity to make personal contact with the workers and develop trust within the community.

While union bureaucrats had only sporadic contact with the factory employees, Kassák and Balázs understood both the rules of trade unionism and the everyday realities of workers.[18]In the factory, Balázs worked with the other weavers and occupied the same place in the wage hierarchy. At the same time, she was also familiar with the socialist organizational structure and actively participated in union work.[19] Kassák, compared to Balázs, worked somewhat more isolated in the tool shop but he often engaged in confrontation within the Metalworkers’ Union, and these conflicts pushed him to look for camaraderie among non-union members. According to Kassák, as a result of the efforts they put into community building with Balázs: “The hooligan factory became the strongest unit of the socialist organization.”[20]

Nevertheless, neither the economic nor the legal environment allowed even unionized workers to overcome their precarious conditions in the jute factory. When the 1908 strike failed, Kassák and Balázs were both immediately dismissed and neither of them got employed as a factory worker again.[21]

References:

[1] This blog post was written in the framework of the project “Digital critical edition of the correspondence of Lajos Kassák and Jolán Simon between 1909 and 1928 and new perspectives for modernity research” (OTKA FK-139325).[2] Jute is a bast fiber produced in South Asia, mainly in India, and it was mainly used to make packaging materials, bags, and ropes.

[3] The quotations are taken from Kassák’s Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man]. The first three volumes of Kassák’s novel originally appeared in a Budapest-based modernist literary journal Nyugat as a sequel, between 1924 and 1927. See the relevant section in Lajos Kassák, Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Nyugat, January 16., vol. 20, no 2., (1927), see: https://epa.oszk.hu/00000/00022/00411/12809.htm (Translation by the author).

[4] Gyűlési tudósítások [Meeting reports], Népszava, April 27, 1907, 12. (Népszava was the official journal of the Social Democratic Party)

[5] Idős harcosok emlékeznek [Old fighters’ recollections], Famunkás, June 4., 1958, 4.

[6] Budapesti Hírlap, May 9, 1908.

[7] “…ezek a nők Újpest környéki parasztok voltak, akiknek van egy kis földjük vagy családi gazdaságuk, csak olyan mellékes életük a gyári munka, s ezért eddig semmiféle mozgalomba nem lehetett őket bekapcsolni […these women were peasants from the Újpest area, who had a small plot of land or a family farm, factory work was only secondary for them, and therefore they would not get involved in any labour movement activity so far.]” (in: Kassák, Egy ember élete).

[8] Farkas József, “Az ipari és mezőgazdasági munkásság szakmai szervezkedése és bérharca 1896–97-ben [Industrial and agricultural workers’ professional organisation and their wage struggle in 1896–97]” Tudományos Szocializmus 15, 1978, 17–64. and Fonó Zsuzsa, “Az ipari nőmunkások helyzetéről a századfordulón [The situation of women in industrial labour at the turn of the century]” Budapest: SZEKI, 1974.

[9] “Az újpesti jutagyár bérrabszolgái [Wage-slaves of the jute factory in Újpest]” Népszava, July 14, 1912, 11.

[10] “Tőke és munka [Capital and labour]” Népszava, June 23, 1903, 5.

[11] “A jutagyári sztrájk [Strike at the jute factory]” Népszava, May 30, 1903, 3.

[12] Excerpt from Kassák’s Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Nyugat, 1927.

[13] The term “coolie” was first used to refer to East-Asian wage labourers whose cheap labour was intended to replace slave labour on colonial plantations. The Hungarian public was already familiar with the imperialist practice of coolie import for a long while, and by 1927, when Kassák first published this section of his novel, the term had become synonymous with the global lumpenproletariat, it still carried obvious racial connotations, at the same time it was widely used for addressing workers subjected to the most inferior labour conditions.

[14] Kelly, John, “Trade Unions and Socialist Politics” London: Verso, 1988, 128–147. On the gender aspects of the history of the textile industry: Els Hiemstra-Kuperus, Lex Heerma van Voss, and Elise van Nederveen Meerkerk, ‘Introduction,’ in eds. Heerma van Voss, Hiemstra and Van Nederveen Meerkerk, The Ashgate Companion to the History of Textile Workers, 1650–2000, Aldershot: Ashgate 2010, 1–16.

[15] Excerpt from Kassák’s Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Nyugat, 1927.

[16] Excerpt from Kassák’s Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Nyugat, 1927.

[17] Excerpt from Kassák’s Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Nyugat, 1927.

[18] On sectional (what are these?) conflicts during strike-movements: Bódy Zsombor “A hétköznapi élet története: Munkás visszaemlékezések a századforduló idejéből [The story of everyday life: workers’ reminiscences from the turn of the century]” in A mesterségek iskolája, Tanulmányok Bácskai Vera 70. születésnapjára eds. Zsombor Bódy, Mónika Mátay, and Árpád Tóth, Budapest: Osiris, 2000, 275–293.

[19] In 1908, she participated as a member of the electoral committee at the annual congress of the Textile Workers’ Federation and she held speeches at the organization’s meetings in several districts of Budapest and agitated in favor of the trade union.

[20] Excerpt from Kassák’s Egy ember élete [The Life of a Man], Nyugat, 1927.

[21] In The Life of a Man, Kassák later writes of Balázs that she opened a coffee-tasting shop, and then she left Budapest and moved to the countryside where she started working as an actress. Kassák, in the spring of 1909, set off for Paris on foot.

Illustrations:

- The jute factory on Map of Budapest, Manó Kogutovicz, 1908. Wikimedia Commons. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Budapest_sz%C3%A9kes-f%C5%91v%C3%A1ros_eg%C3%A9sz_ter%C3%BClet%C3%A9nek_t%C3%A9rk%C3%A9pe.jpg. An arrow is added by the author.

- The “Juta-houses”. Built in 1912 for the workers of the jute factory. Budapest, XIII. district. Author’s Photo (2023).

Sára Bagdi has been working for the Kassák Museum since 2021 as a junior research fellow. There, she co-curated the exhibition “Wonderful Story? An Avant-Garde Artist Couple: Erzsi Újvári and Sándor Barta.” She gained an MA from the Department of Art History of ELTE in 2018 and completed her master’s studies in Aesthetics in ELTE in 2019. At present, she is a doctoral student in the same institution, partially pursuing her research at the University of Hamburg as a DAAD scholarship holder. Her research areas are workers’ culture between the two world wars, labour activism, and primitivism.