by Adrienn Kácsor

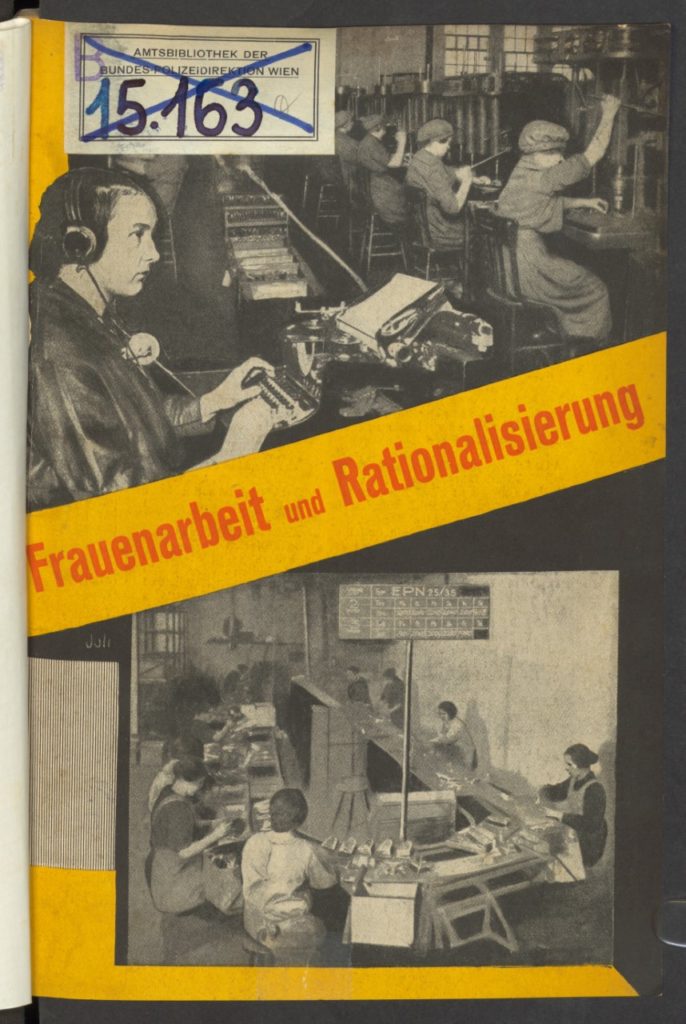

An obsolete library label in the upper left corner of the cover of Frauenarbeit und Rationalisierung [Women’s Labour and Rationalization] marks the interest the Viennese State Police once held in a book about women’s labour from the late 1920s (fig. 1).[1] The book is a prototype of the transnational agitprop production that the Communist International pursued between the two World Wars.[2] Written by Isa Strasser, a Moscow-based member of the Communist Party of Austria (KPÖ), the book appeared in 1927 with an eye-catching cover designed by Jolán Szilágyi (1895–1971), a Hungarian communist artist dispatched from Moscow to Berlin to participate in the illegal and semi-legal propaganda activities of the Comintern. Szilágyi montaged the cover from photographic images of women immersed in their work. Yet, the photos have an eerie quality to them, encapsulating some of the ambiguous ideas that circulated in the orbit of the Comintern regarding women’s labour. To paraphrase Strasser’s introduction to the book: the feminine workforce was extremely valuable, except that capitalism misused women’s bodies as simply a cheaper alternative to men’s labour.[3] The only solution, Strasser’s introduction suggests, was to change the oppressive working conditions in which women laboured in capitalism. Accordingly, Szilágyi’s cover simultaneously demonstrates women’s focus and capacity to perform meticulous labour, as well as their enslavement by their work conditions. The woman seated at a typewriter on the upper left, for instance, is quite literally wired into the machine that is her primary work tool. Moreover, her spatial and physical isolation mimics the solitude of the cyborg-like women shown in the upper right, whose bodies look like mechanic extensions of the handles they operate.

It is rather ironic that the names of the two women primarily responsible for the content and look of this book on women’s labour are absent from the cover. Strasser’s name is at least credited on the title page; Szilágyi’s name, however, is altogether missing from the publication. The only trace that identifies Szilágyi as the artist-designer of the cover is the unassuming insertion of her signature. “Joli,” her artistic pseudonym, appears in a small white caption on the left side of the cover, right under the diagonally displayed title radiantly scripted in red on yellow background. The way in which “Joli” becomes the sole marker of Szilágyi’s artistic labour gestures to the working conditions of invisibility in which communist artists laboured in one of the cultural and political centers of Europe in the 1920s. Yet Szilágyi’s story of invisibility, as this blog post shows, gets further complicated by the fact that she was a migrant woman in Weimar Germany. With the help of communist camouflage techniques, Szilágyi essentially inscribed her German artistic record into historical anonymity.[4] Her case therefore vividly speaks to the methodological difficulties art historians face when studying the ephemeral aesthetic production of the radical left in interwar Europe, especially when produced by migrants and women.

Having a pseudonym was the name of the game for members of the international communist movement, particularly in countries such as Weimar Germany, where the legal status of the communist party and its members was often precarious.[5] Less visibility simply meant more safety—the primary reason why German communist publications from the 1920s and the first years of the 1930s are laden with political caricatures that are either altogether anonymous or signed by abbreviations or other kinds of pseudonyms. Gü or Red, for instance, are among the most common signatures that appeared on the pages of Roter Pfeffer [Red Pepper], the high-quality satirical magazine published by the German Communist Party (KPD) in Berlin in 1932-33.[6] Such pseudonyms were part of the local communist code language. Around the KPD, everyone would know that the extraordinarily colorful and witty cartoons on the covers of Roter Pfeffer were created by Günther Wagner or Alfred Beier-Red, some of the most popular leftist caricaturists in Berlin at the time. Yet, the pseudonyms would offer—at least some—protection from the German authorities.

Given that Szilágyi was registered with the authorities under an entirely different fake name, it was not a bad idea to use her given name as her artistic pseudonym in Weimar Germany. Yet I cannot stop thinking about how Szilágyi’s choice of “Joli,” a nickname version of Jolán, provided for a somewhat infantilizing pseudonym. Judging from her memoir, it was common practice to use informal nicknames especially—but not exclusively—among women members of the Hungarian leftist diasporas in Berlin, Vienna, and Moscow too. Szilágyi often recorded encounters in which she was called “Joli” or even “Jolika,” with a Hungarian diminutive suffix added at the end.[9] Such nicknames could concurrently mark familiarity, friendship, and even intimacy, along with the operations of unequal social hierarchies formed by gender, age, experience, and position in the workers’ movement. “Joli” strikes me as both a surprisingly unpretentious and gendered artist’s name when compared to the pseudonyms that her male Hungarian comrades picked for themselves. Artist Sándor Leicht (1902–1975), for instance, went for Alex Keil, a name with much of the political symbolism of power and masculinity as the German equivalent of “wedge.” As if inscribing himself as a creative weapon in the hands of the party, artist László Dallos (1901–c.1947), another one of Szilágyi’s close friends, went for Griffel—the German word for “slate pencil.”

I wonder, however, how much of the gendered nuances embedded in Szilágyi’s nickname were legible to non-Hungarian speakers, if any. She may have picked “Joli” as her artistic pseudonym in Germany for its simplicity and lack of characters that would be foreign to the German language. Her German comrades certainly had difficulties with her Hungarian name. Even the short “Joli” turned out to be problematic, as demonstrated by the misspelling of her name in extent historical records of the Association of the Revolutionary Artists of Germany (ARBKD), founded in Berlin in 1928.[10] According to the minutes of the first meeting held on January 30, 1928, for instance, the following artist-comrades were present at the foundation of the ARBKD: “Yoli Shilagil, John Heartfield, Heinz Tischauer, Mia Tischauer, Alex Keil, Alfred Beier, Spotarcyk, Günter Wagner, Urban, Gehrig-Targis. Heinrich Vogeler entschuldigt. [Heinrich Vogeler is excused].”[11] The almost complete distortion of Szilágyi’s name as “Yoli Shilagil” aptly illustrates how much sense her German comrades could make of her foreign name.

The deformation of Szilágyi’s name is certainly one of the reasons why she has remained invisible in the histories of the ARBKD, despite all the extensive research projects that both East and West German art historians carried out from the 1960s.[12] The three-page-long, typed minutes of the 1928 meeting are among the most elementary historical documents of the ARBKD. They exist in typed and xeroxed copies in major archives of German art.[13] Yet, no “original” document exists in the strictest sense of the world—and it likely never did. The minutes were most probably created after 1945 by Franz Edwin Gehrig-Targis (1896–1968), one of the artists present at the 1928 meeting. To elevate ARBKD from decades of historical neglect, Gehrig-Targis seems to have typed up his handwritten notes from his private notebooks and turned them into a historical document.[14] I suspect that Gehrig-Targis had no idea who Szilágyi was, neither in 1928 nor after World War II. “Yoli Shilagil” thus never got corrected.

In her Hungarian memoir published in the 1960s, Szilágyi vividly described her life in Berlin during the Weimar era. It is striking how much of her work in Berlin could only be remembered and described because she had neither documents about most of her activities, nor access to much of the work she made in Berlin.[15] Indeed, without the details in her memoir about her activities for the ARBKD, I would probably not suspect her name behind the mysterious “Shilagil.”[16] As this blog post sought to demonstrate, the communist tactic of invisibility produced an unsolicited and lasting effect on an artist who laboured in Weimar Germany as a migrant woman. Szilágyi, in effect, conditioned her own historical invisibility as an artist.

References:

[1] Isa Strasser, Frauenarbeit und Rationalisierung [Women’s Labour and Rationalization] (Moscow; Berlin: Verlag der Roten Gewerkschafts-Internationale; Führer-Verlag, 1927).

[2] The Communist International, also known as the Third International or the Comintern, was the international organization of communist parties from all around the world, founded by Lenin in 1919. Until the end of its operations in 1943, the Comintern funded a wide array of agit-prop and educational activities globally. For recent scholarship on the aesthetic productions of the Comintern, see: Amelia Glaser, Steven S. Lee (eds.), Comintern Aesthetics (Toronto: University of Toronto Press, 2020). Frauenarbeit und Rationalisierung was published by the Red International of Labour Unions, a Moscow-based Comintern organization commonly known as the Profintern, and distributed in Berlin by the Comintern-affiliated Führer-Verlag.

[3] Strasser, Frauenarbeit und Rationalisierung, 5-6.

[4] For the most comprehensive account of Szilágyi’s work in Weimar Germany, see: Wolfgang Hesse, “Jolán Szilágyi und die Kunst der Straße” [Jolán Szilágyi and the Art of the Street], in Der rote Abreißkalender: Revolutionsgeschichte als Wandschmuck [The Red Tear-off-the-Page Calendar: The History of the Revolution as Wall Decoration] (Lübeck, 2019), 42–69. Available in open access: https://slub.qucosa.de/api/qucosa%3A34691/attachment/ATT-0/ [Last accessed on March 1, 2023]. Note also the 1971 solo exhibition that was organized in East Berlin in the summer of 1971, with a two-page, fold-out exhibition pamphlet with no illustrations or exhibition checklist: Ausstellung Malerei und Grafik Jolán Szilágyi [Exhibition Painter and Graphic Artist Jolán Szilágyi], exhibition pamphlet, Neue Berliner Galerie, July 8 – August 1, 1971. Szilágyi passed away in Budapest on the opening day of her long-awaited Berlin exhibition, on July 8, 1971. Most recently, the Berlinische Galerie’s exhibition on Berlin’s Hungarian diaspora included a few works from Szilágyi’s German oeuvre: Ralf Burmeister, Thomas Köhler, László Baán, András Zwickl (eds.), Magyar Modern: Hungarian Art in Berlin, 1910–1933 (Munich: Hirmer Publishers, 2022).

[5] On the Comintern lifestyle of secrecy and conspiracy, see Brigitte Studer, The Transnational World of the Cominternians (Palgrave, Macmillan, 2015).

[6] For a study of the communist politics of satire in Weimar Germany, including a brief institutional history of the periodical Roter Pfeffer, see: Sabine Kriebel, “Left-Wing Laughter,” in Revolutionary Beauty: the Radical Photomontages of John Heartfield (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014), 167-213, especially 178. See some of the covers of Roter Pfeffer digitized from the collection of the Deutsches Historisches Museum at: https://www.deutsche-digitale-bibliothek.de/item/TMMGROG4FLR64PSISYDXVRTD37KOTO23 [Last accessed on March 1, 2023].

[7] On the history and culture of the Hungarian Bolshevik Republic, which lasted only for 133 days in the spring and summer of 1919, see in English: Bob Dent, Painting the Town Red: Politics and the Arts During the 1919 Hungarian Soviet Republic (London: Pluto Press, 2018).

[8] Jolán Szilágyi Szamuely Tiborné, Emlékeim [My Memories] (Budapest: Zrínyi Katonai Kiadó, 1966), 163. In addition to her memoir, see the pseudonym Margareta Dobry mentioned in the political autobiographies Szilágyi submitted to the Comintern: RGASPI Fond 495, Opis’ 199, Delo 2897: Lichnoe delo Siladi Iolan [Personal Folder of Jolán Szilágyi]

[9] See, for instance, a recollection from her Viennese exile, when a fellow Hungarian comrade complimented Szilágyi on her vivid imagination with the words: “Jolika! Magának rettenetesen konkrét fantáziája van!” [Jolika! You have a horribly concrete imagination!], in: Szilágyi, Emlékeim, 135.

[10] On the history of the ARBKD, also known as ASSO, see: Rüdiger Grimkowski, “Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler Deutschlands” [Association of the Revolutionary Artists of Germany] https://www.dhm.de/lemo/kapitel/weimarer-republik/kunst/assoziation [Last accessed on March 1, 2023]; Kunst als Waffe: die ‘Asso’ und die revolutionäre bildende Kunst der zwanziger Jahre [Art as Weapon: The ‘ASSO’ and the Revolutionary Art of the Twenties], exhibition catalog, Nürnberg, May 29-June 20, 1971 (Düsseldorf : DKP, 1971); Jürgen Kamer, “Die Assoziation revolutionärer bildender Künstler Deutschlands (ARBKD)” [The Association of the Revolutionary Artists of Germany (ARBKD)], in Wem gehört die Welt: Kunst und Gesellschaft in der Weimarer Republik [Whom Belongs the World to: Art and Society in the Weimar Republic], exhibition catalog, Berlin, August 21-October 23, 1977 (Berlin: Die Neue Gesellschaft für Bildende Kunst, 1977), 175-204.

[11] “Protokoll der I. Versammlung (Gründungsversammlung) der Arbeitsgemeinschaft kommunistischer Künstler Deutschlands” [Minutes of the First Meeting (Foundation) of the Working Group of the Communist Artists of Germany], January 30, 1928, three pages, typed. Xerox copy in Zentralarchiv, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB), Sammlung “Proletarischen Kunst – ASSO” [Collection of Proletarian Art-ASSO]. Wolgang Hesse has also noted the misspelling of Szilágyi’s name: Hesse, “Jolán Szilágyi und die Kunst der Straße,” 49.

[12] Two major exhibitions that resulted from these research projects are the above referenced Wem gehört die Welt exhibition in West Berlin in 1977, and its pair in East Berlin: Revolution und Realismus: Revolutionäre Kunst in Deutschland 1917 bis 1933 [Revolution and Realism: Revolutionary Art in Germany 1917–1933], exhibition catalog, Altes Museum, Berlin, November 8, 1978–February 25, 1979 (Berlin: Staatliche Museen zu Berlin, 1978).

[13] For my research, I consulted the copies available in the collections of the Akademie der Künste (AdK) and the Zentralarchiv of the Staatliche Museen zu Berlin (SMB).

[14] An anonymous handwritten note on the back of the third page of the January 30, 1928 minutes at the Zentralarchiv warns that the xerox is not made out of the original document. Based on information that this unknown author received from Gehrig-Targis in January 1962, there was altogether no original document: „…Auskunft von Gehrig-Targis Anfang Jan. 1962 ist dies tatsächlich kein Original-Manuskript, sondern von G-T nach 1945 geschrieben nach seinen eigenen Taschenbuchnotizen von damals.” [Information from Gehrig-Targis early Jan. 1962 this is actually not an original manuscript but written by G-T after 1945 based on his own notes of that time].

[15] Some of her drawings and maquettes for covers or press illustrations miraculously survived both her escape from Berlin to Moscow in 1933 and the many twists and turns of her Soviet life between 1933 and 1948. Along with her surviving works, Szilágyi returned to Budapest in 1948. Most of these works entered the collections of the Hungarian National Gallery and the Museum of the Workers’ Movement in the 1960s and ‘70s.

[16] See her recollections of the ARBKD especially in the memoir’s chapter on the year 1928: Szilágyi, Emlékeim, 209-214.

Illustrations:

- Jolán Szilágyi (Joli), Cover design for Frauenarbeit und Rationalisierung [Women’s Labour and Rationalization], 1927. Image Credit: Österreichische Nationalbibliothek, Vienna. Despite the best efforts, the author was unable to contact the copyright holders.

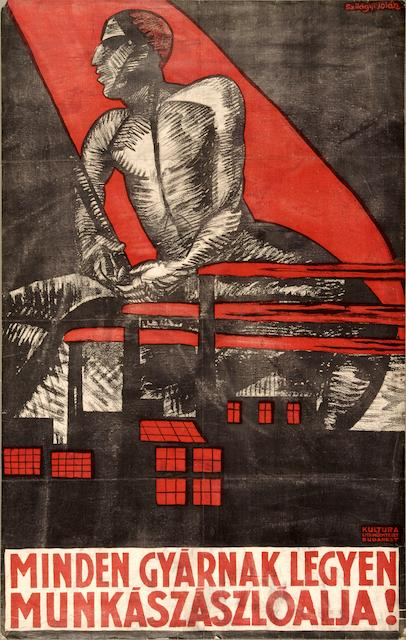

- Jolán Szilágyi, MINDEN GYÁRNAK LEGYEN MUNKÁSZÁSZLÓALJA! [Every Factory Shall Have a Workers’ Battalion!], 1919. Image Credit: Hungarian National Museum, Hungary – CC BY-NC-SA. https://www.europeana.eu/item/2064401/_mnm_MNMMUSEUM684992

Adrienn Kácsor is a predoctoral fellow at the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, and a Ph.D. candidate in the Department of Art History at Northwestern University. Her research on Jolán Szilágyi has been generously supported by the Mellon Fellowship for Dissertation Research in Original Sources, granted by the Council on Library and Information Resources; The Social Science Research Council’s International Dissertation Research Fellowship, with funds provided by the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation; and the Leonard A. Lauder Research Center for Modern Art at The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.