by Veronika Helfert

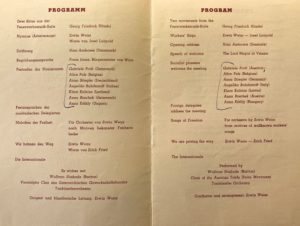

In July 1957, the Fifth Congress of the Socialist International was held in Vienna. A few days before, the Women’s Central Committee of the Austrian Socialist Party held a celebratory meeting: It was the 50th anniversary of the First Socialist Women’s Conference in Stuttgart in 1907. Among others, seven women who had been present in that pioneering Stuttgart conference were invited: Angelica Balabanova (Italy), Klara Kalnins (Latvia), Anna Kéthly (Hungary), Alice Pels (Belgium), Anna Stiegler (Germany), and the two Austrians Anna Boschek and Gabriele Proft (see program).

Program of the celebratory meeting on 29 June 1957 in Vienna, IISH Amsterdam, ICSWD Collection.

The 1907 conference in Stuttgart was the founding moment of a more pronounced and public engagement of socialist and social democratic women in Europe active for political and social women rights.[1] These women established an international organisation with a secretariat occupied by the known German socialist Clara Zetkin. The second conference in Copenhagen 1910 initiated the Women’s International Day to promote women’s rights like women suffrage – as universal male suffrage has been introduced in many European countries since the beginning of the 20th century. The socialist women’s International institutionalised existing networks and friendships between socialist women and sought to further the diverse working women’s agendas.

In 1957, twelve years after the end of the Second World War, two years after the reestablishment of the Socialist Women’s International, and during the Cold War, the program pictured above shows how efforts were made to continue the traditions of the interwar period. This blog post focusses on Gabriele Proft, born Jirsa (1879–1971),[2] one of the “pioneer women” present at the conference. Her involvement goes back to the beginnings of the trade union and socialist women’s movement in the Habsburg Monarchy. The correspondence surrounding this meeting, held in the ICSDW archives in Amsterdam, shows the deep connections and friendships between women activists, some of whom had known each other for half a century, and were meeting again under changed world political auspices. A retracing of Proft’s life makes obvious that her story connects with many other life trajectories. These entanglements cannot be followed up here. A history of (international) socialist female friendships would still largely have to be written.

When Gabriele Proft participated in the Stuttgart conference, she was only at the beginning of her own career, one that led her from the washing troughs of a laundry in Opava/Troppau (now Czech Republic) to the splendorous halls of the Austrian Parliament. After the death of her mother, Gabriele Jirsa, the daughter of a shoemaker, started to support the family at 13 years old. Aged 17, like so many of her peers, she came to the imperial capital, Vienna, and gained her income as servant and a textile worker. In 1900, only 13 percent of Viennese servants were born in Vienna, more than 50 percent immigrated from a different crownland – many of them from Bohemia and Moravia.[3] Proft – she married the metalworker Karl Anton Proft in 1899 and divorced him in 1916 – joined the Worker’s Educational Association (Arbeiter-Bildungsverein) Apollo, as only one of “five or six” women, as she later recalled.[4] These types of associations were common at the beginning of the Austrian labor movement: they combined social motives with educational activities (lectures, reading circles, etc.) and economic purposes, such as support benefits. Many of these associations were under surveillance and were repeatedly dissolved by the police. In the 1890s, their importance declined, while that of trade unions increased.

In 1902, Gabriele Proft was among the founding members of a social democratic trade union for home-based women workers – mainly seamstresses and laundresses – and domestic servants (Verein der Heim- und Hausarbeiterinnen) and served as its treasurer. There she worked together with Anna Boschek (1874–1957), who served as a chairwoman. Boschek was already a very prominent figure in Austrian social democracy as a noted female trade unionist and founding member of the Women’s Committee of the party SDAP, and became a “leading representative of the IFTU Women’s International”[5]

in the interwar period. Although the organization was run by prominent activists and had many attractive benefits, such as legal aid, job services, and financial support for childbirth and illness, it remained small in number and was eventually swallowed up by the union for domestic workers “Unity” (Verband der Hausgehilfinnen – Einigkeit), which was founded in 1911.

Proft profited from her union activism and started to attend courses at a workers’ school (Arbeiterschule), where she was not only able to catch with some elementary education, but also learned skills that were important for a political party career, such as giving speeches. Only one year after Stuttgart, she shifted her focus from trade unionism to political work and became the secretary of the Women’s Committee of the Social Democratic Party. Her political activism was steady and long lasting regardless the political ruptures of this century. On a national level, she worked in the women’s committee, heading after 1945. She was a leading party member rising to the position of a vice chair, and was one of the first women to move into Parliament in the newly founded Austrian Republic, in 1919. There she would serve until 1934 and then again from 1945 until her retirement in 1953.

Women’s Committee and Lower Austrian Provincial Committee, 1917. In the first row on the extreme right: Gabriele Proft, via Wikimedia.

Gabriele Proft was one to be found on the left wing of the SDAP. This was evident not least from her pacifist stance during the First World War and her connections to young, more radical women workers. One of her consistent responses to problems they had was organizing – as workers in trade unions and as women in the political organisation.[6] The separate organization of women was quite controversial in Social Democracy: Proft herself saw it as necessary in order to better agitate proletarian women, but also to articulate specific problems. Her 1912 description of her own work in the Verein der Heim- und Hausarbeiterinnen as one of the few organizations for women only can be read as an emancipatory experience. As a member of Parliament, Gabriele Proft introduced bills and issues aimed, among other things, at legal improvements. One of those proposals was the rather radical novella of the regulation of married names in 1924, which also included the possibility of the husband taking the wife’s name.[7]

The year 1933 marked a radical change in the political culture of the First Republic and in Gabriele Proft’s life. The Christian Social Chancellor Engelbert Dollfuß, who was in a coalition with the democratic arm of the right-wing paramilitary troops Heimwehren, took advantage of a parliamentary stalemate for an authoritarian restructuring of the state. The communist and national socialist parties were banned first, as was the SDAP’s paramilitary organization. In 1934, a civil war broke out that lasted only a few days. Numerous leading members of the SDAP fled the country or were imprisoned – among them Gabriele Proft.[8]

After her release, she joined the Revolutionary Socialists and became involved in the resistance, as did many other women communists and social democrats. Due to the policy of recatholicization and remasculinization of the Austrofascist “Corporate State” (“Ständestaat”), there was no place for her in politics anyway. The political equality of women and men had been abolished. Parties and free trade unions were dissolved. She was repeatedly imprisoned not only under Austrofascism, but also after the National Socialist seizure of power. In 1944, for example, she was incarcerated and held in the Lanzendorf concentration camp until liberation.

In 1945 Gabriele Proft published a booklet, remembering the comrades that had died “on the scaffold”,[9]

mapping out the situation of the working women and housewives, and calling them to get organized and to rebuild a democratic, peaceful state. Proft warned against a counter-revolution, placing herself very clearly on the social democratic side of what would soon be a frontier in the Cold War on the national as well as international level. Having attended the Socialist Women’s International conference already at the beginning of the century, she became highly active in reactivating the International Council of Social Democratic Women (ICSDW) – an organisation she stayed very close to until her death in 1971. Only a few years before, the ICSDW established a Fund at her name, that still exists today.

References:

[1] For further information see Susan Zimmermann, “A Struggle over Gender, Class and the Vote: Unequal International Interactions and the Formation of the ‘Female International’ of Socialist Women (1905–1907),” in Gender History in a Transnational Perspective: Networks, Biographies, Gender Orders, ed. by Oliver Janz and Daniel Schönpflug (Berghahn Books 2014), pp. 101–126. The German Friedrich Ebert Stiftung published the Reports to the First International Conference of Socialist Women online.

[2] On Gabriele Proft see among others Gabriella Hauch, Frauen bewegen Politik: Österreich 1848–1938 [Women move politics: Austria 1848–1938], (Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2009); Marie-Luise Angerer, “Gabriele Proft. ‘Faust soll zwischen 1480 und 1540 gelebt haben`,” in “Die Partei hat mich nie enttäuscht …” Österreichische Sozialdemokratinnen [“The party never dissapointed me …” Austrian women social democrats], ed. by Edith Prost (Vienna: Verlag für Gesellschaftskritik, 1989), pp. 187–221; and https://www.geschichtewiki.wien.gv.at/Gabriele_Proft.

[3] Jessica Richter, Die Produktion besonderer Arbeitskräfte: Auseinandersetzungen um den häuslichen Dienst in Österreich (Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts bis 1938) [The Production of a Particular Workforce: Disputes over Domestic Service in Austria (Late 19th Century to 1938)] (Doctoral Dissertation: University of Vienna, 2017), pp. 21–23.

[4] Gabriele Proft, “Ein Beitrag zu unserer Jubiläumsfeier” [“A Contribution to our Anniversary Celebration”], in Gedenkbuch: Zwanzig Jahre Arbeiterinnenbewegung [Commemorative Book: Twenty Years of the Women’s Workers’ Movement] (Vienna: Wiener Volksbuchhandlung, 1912), pp. 153–158, here: p. 156.

[5] Susan Zimmermann, Frauenpolitik und Männergewerkschaft: Internationale Geschlechterpolitik, IGB-Gewerkschafterinnen und die Arbeiter- und Frauenbewegungen der Zwischenkriegszeit [Women’s Politics and Men’s Trade Unionism: International Gender Politics, Female IFTU Trade Unionists and the Workers’ and Women’s Movements of the Interwar Period] (Vienna: Löcker, 2021), p. 134.

[6] Gabriele Proft, “Wie organisieren wir die neuen Arbeiterinnen?” [“How Are We Going to Organize the New Women Workers?”], Arbeiter-Zeitung (29.08.1916), p. 6.

[7] Nina Reitmeier, “Zur Politik des Namens: Politische Kontroversen um die namensrechtliche Gleichstellung in Österreich” [“On the Politics of Names: Political Controversies about Equality in Name Law in Austria”], in Politik und Geschlecht: Dokumentation der 6. Frauenringvorlesung an der Universität Salzburg, WS 1999/2000 [Politics and Gender: Documentation of the 6th Women’s Ring Lecture at the University of Salzburg, Winter Term 1999/2000], ed. by Elisabeth Wolfsgruber (Innsbruck: Studienverlag, 2000), pp. 167–190, here: p. 172.

[8] Irene Bandhauer-Schöffmann, “Nach der Zerstörung der Demokratie: Politische Partizipation im Austrofaschismus (1933/1934–1938)” [“After the Destruction of Democracy: Political Participation under Austrofascism (1933/1934–1938)]”, in “Sie meinen es politisch!” 100 Jahre Frauenwahlrecht in Österreich: Geschlechterdemokratie als gesellschaftspolitische Herausforderung [“They mean it politically!” 100 Years of Women’s Suffrage in Austria: Gender Democracy as a Sociopolitical Challenge], ed. by Blaustrumpf ahoi! (Vienna: Löcker 2019), pp. 177–194.

[9] Gabriele Proft, Der Weg zu uns! Die Frauenfrage im neuen Österreich [The Way to Us! The Women’s Question in the New Austria] (Vienna: SPÖ, 1945), p. 5.

Illustrations:

- Featured photo: Participants at the International Socialist Congress in Zurich: Portrait of Gabriele Proft (1947). Foto: Ernst Koehli. Schweizerisches Sozialarchiv, F 5144-0891-Nb-003.

- Program of the celebratory meeting on 29 June 1957 in Vienna, IISH Amsterdam, ICSWD Collection.

- Women’s Committee and Lower Austrian Provincial Committee, 1917. In the first row on the extreme right: Gabriele Proft, via Wikimedia.