by Selin Çağatay

Trade unions are known as male-dominated structures that historically marginalized women workers’ interests and excluded women from leadership positions. In Turkey, feminist researchers working in the field of gender and labour criticized trade unions for failing to develop strategies that would effectively engage women in labour politics such as union education. They argued that union leaders in Turkey adopted a gender agenda by the pressure they received from international labour organizations, but the structures they created for women workers remained on paper due to a lack of mobilization from below.[1] The picture looks different, however, when one considers the transnational connections established around the union education of women.

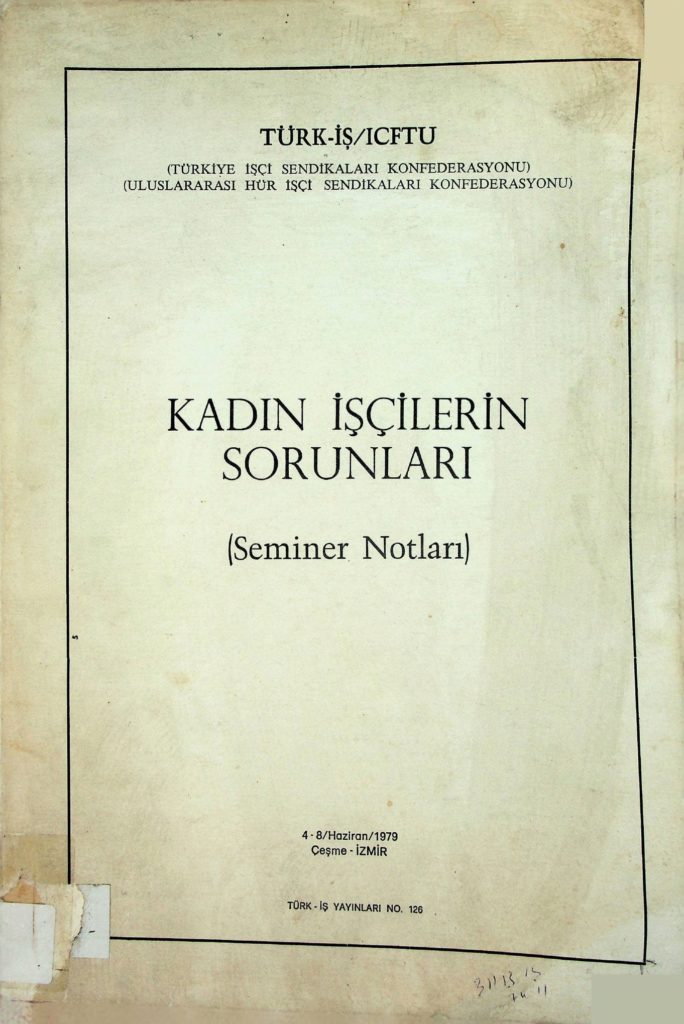

In July 1979, the Confederation of Turkish Trade Unions (Türk-İş) and the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU) co-organized a women’s seminar in Çeşme, İzmir. The four-day event was part of a series of international educational seminars organized collaboratively by Türk-İş and the ICFTU. It brought together union educators and women labour activists and resulted in the formulation of demands by women that shaped the gender politics of Türk-İş in the ensuing years. Taking this seminar as a vantage point, in this blog post I aim to bring to light some of the forgotten history of women’s labour activism and transnational organizing.

Among the educators of the 1979 women’s seminar (hereafter Çeşme seminar), there was a key actor in shaping ICFTU’s gender politics: Marcelle Dehareng. A member of the Belgian Confederation of Trade Unions, Dehareng was the secretary of the ICFTU’s Women’s Committee from its foundation in 1957 until her retirement in 1985. Together with other women such as Esther Peterson (U.S), Sigrid Ekendahl (Sweden), and Maria Weber (West Germany), they were the architects of ICFTU’s policies for women workers including educational programs.[2]

The education of women workers in Turkey, like in Europe,[3] began back in the 19th century, but the real expansion and internationalization of educational activities started in the post-World War II period as this became an agenda item for international trade unions and global governance organizations such as the ILO, UNESCO, OECD, the ICFTU, the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU), and the International Federation of Christian Trade Unions (IFCTU). Thanks to the sustained efforts of the women in the ICFTU Women’s Committee, the ICFTU became the best organized and most dedicated to women’s education out of the three major international trade union organizations.[4] Members of the Women’s Committee also traveled extensively, produced research and travel reports as well as policy proposals that had in/direct implications for the education of women workers in developing countries, and engaged in educational work in the places they visited as Dehareng did in Turkey.[5]

At the Çeşme seminar, Dehareng gave participants a detailed account of the work of the ICFTU Women’s Committee from the 1950s until the present day. Paying special attention to the role of education in the integration of women into trade unions, she urged the national and local unions to build on the foundations that were laid by the trade union movement at the international level to meet “the aspirations of women workers aspiring to dignity and social justice as equal partners to men in society.” This task, she argued, belonged also to “the individual woman who must not shy away from her responsibility as a union member.”[6]

The Çeşme seminar was not the first time that Dehareng visited Turkey. Nor was it the first encounter between the ICFTU Women’s Committee and Turkish women labour activists.

As early as 1953, the ICFTU organized a summer school for working women in La Brévière, France. As the first contact between Turkish and ICFTU women, two representatives from Turkey participated in this event that shaped ICFTU’s future work on working women. It was this summer school that led to the foundation of the ICFTU Women’s Committee.[7]

In 1963, a few months after the ICFTU Conference on Women Workers’ Problems that took place in Vienna,[8] Dehareng attended an educational seminar for women trade unionists in İzmir co-organized by Türk-İş and the ICFTU, where she lectured on the problems facing women workers and their role in the trade union movement. Before heading to Athens, she also held meetings with women trade unionists in Ankara, the capital of Turkey.[9] In 1968, Dehareng visited Turkey again, this time together with Petronella Tegelaar (Netherlands), another member of the ICFTU Women’s Committee. During each visit, Dehareng communicated to women trade unionists the recent work of the Women’s Committee and the broader developments concerning women workers on the international scale.

Published since 1963, the monthly journal of Türk-İş, Türk-İş Dergisi, regularly reported on the ICFTU’s policies on women workers, the work of the Women’s Committee, and the visits of ICFTU educators to Turkey. News of the Women’s Committee’s meetings and conferences were often followed by articles on the issues of women workers in Turkey. In line with the importance the Women’s Committee gave to education, these articles repeatedly emphasized the need for vocational, literacy, technical, and trade union training for women. For example, following the acceptance of the ICFTU “Charter of Rights of Working Women” in 1965, Türk-İş research officer Gül Neş’e Kutlu published a series of articles, focusing each month on a different aspect of women workers’ issues. This way, the agendas of activists at national and local levels resonated with those at the international level.

Not only news and demands but also methods of organizing traveled transnationally. Under Dehareng’s guidance, the seventy women labour activists who attended the Çeşme seminar were divided into small groups to discuss specific topics such as problems concerning social rights, health-related issues, and union- and workplace-related problems. This method of dividing into small groups and formulating demands without the participation of the educator was one of the recommendations made in the “Taljöviken Report: A Programme of Action,” prepared in 1977 at the ICFTU Women’s Committee meeting in Taljöviken, Sweden, and accepted at the ICFTU’s 70th Executive Board meeting, to facilitate women’s active participation in trade unions.[10]

Following the Çeşme seminar, some of the trade union women who attended the seminar gathered in Ankara to prepare a final report based on the minutes taken during the small group discussions. This report included the many demands raised by the seminar participants to improve women’s work conditions and labour rights and enable their involvement in decision-making processes in trade unions. Importantly, the report called for the immediate establishment of a women’s bureau in Türk-İş that would resemble the ICFTU’s Women’s Committee to which women’s bureaus of Türk-İş member unions would report.[11]

A Women Worker’s Bureau was indeed established in Türk-İş in 1980 but in collaboration with another international partner. Instead of the ICFTU, the American-Asian Free Labour Institute (AAFLI), a member institute of the American Federation of Labor and Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL–CIO), funded the Bureau and its educational activities throughout the 1980s. Yet, the ICFTU’s educational principles on women workers continued shaping the work of the Bureau since women who attended the Ceşme seminar carried out its activities. For example, Rahime Akdoğan, who represented the Union of Sales Assistants and Office Workers of Turkey (Tez-Büro-İş) at the Ceşme seminar, became first a specialist and then the chief officer of the Türk-İş Women Workers Bureau. She stayed in this position until 1989 and trained hundreds of women labour activists in Türk-İş member unions nationwide.[12]

In 1990, Türk-İş went back to collaborating with the ICFTU in financing women’s education, and activists involved in the Türk-İş Women Workers’ Bureau with their counterparts in the ICFTU Women’s Committee. Activists engaging in this reestablished collaboration did not remember, or perhaps did not even know, about the prior work of the ICFTU Women’s Committee in Turkey. At the Türk-İş Women Workers’ Bureau, there was a new generation of experts and activists who collaborated with feminist scholars of gender and labour in addressing the problems of working women. On the ICFTU side too, there was a new generation of feminists active in the Women’s Committee.[13]

Throughout the 1990s, members of the ICFTU Women’s Committee such as Elsa Ramos and Adrian Taylor visited Turkey several times. In 1991, Türk-İş affiliated activists Nilüfer Gököz and Yaşar Seyman attended the 5th ICFTU World Women’s Conference in Ottawa. In 1994, Seyhan Erdoğdu and Füsun Tümsavaş followed the 6th ICFTU World Women’s Conference in the Hague. While these events were widely covered in the pages of Türk-İş Dergisi, the journal on no occasion mentioned similar encounters between Türk-İş and ICFTU women before 1980. Further research is needed to make sense of how only a decade-long break in transnational collaboration was enough to erase the memory of the past struggles and to understand why, in the first place, Türk-İş switched to collaborating with the AAFLI in the 1980s. Further research should also address how global inequalities and hierarchies affected the struggles of and the collaboration between women labour activists in local, national, and international trade unions.

By tracing the history of transnational connections in trade union women’s education, a new and nuanced meaning can be given to interpretations that are taken for granted in national histories. When multiple – national and international – sources are read together, we can see that the developments on women’s education in Türk-İş were considerably entangled with those in the ICFTU and its Women’s Committee. This does not mean that at the local and national levels Türk-İş leaders or women labour activists have copied the demands produced at the international level. Rather, this insight serves as an example of how transnational influence and exchange can enable and facilitate local politics. Thanks to such influence and exchange, Türk-İş leaders were persuaded to address the issues of women workers. Yet, this should not be seen only as a top-down imposition by international trade union organizations, as an earlier generation of feminist scholars interpreted. It was, at the same time, the outcome of many years of hard work by women labour activists who had to challenge and struggle against patriarchal attitudes in their respective unions and other local, national, and international fora.[14] Learning about and from activists’ struggles elsewhere encouraged those in Turkey to voice their demands with more confidence and determination.

Education was key for including women in labour struggles and improving their position in trade unions. In this particular case, we saw how transnational connections between women labour activists in Türk-İş and the ICFTU have impacted trade union women’s education in Turkey. The history I recovered here is a small part of a much bigger, multi-actor mobilization for including women workers in paid work, improving their work conditions, and organizing them for labour rights through education. There is still much research to be done to fully reconstruct the history of the long struggle for empowering women through educational struggles transnationally.

Understanding the different ways in which gender equality struggles were waged is necessary for an inclusive feminist history. Luckily, the present generation of researchers is prepared and equipped to carry out this endeavor.

[1] See, for example, Toksöz, Gülay, and Seyhan Erdoğdu. (1998). Sendikacı Kadın Kimliği [Union Woman’s Identity]. Ankara: İmge Kitabevi; Toksöz, Gülay, and Fevziye Sayılan. “Sendikaların Eğitim Programları ve Kadın Çalışanlar [Unions’ Educational Programs and Woman Workers].” A.Ü. Siyasal Bilgiler Fakültesi Dergisi 53, no. 1–4 (1998): 297–306.

[2] The official name of the Women’s Committee was the Consultative Committee for Women Workers’ Questions. It was jointly created by the ICFTU and the International Trade Secretariats (ITS). Richards, Yevette. “Labor’s Gendered Misstep: The Women’s Committee and African Women Workers, 1957–1968.” The International Journal of African Historical Studies 44, no. 3 (2011): 415–42.

[3] Thivend, Marianne. “Gender and Vocational Education in Europe (19th-20th Centuries).” In Encyclopédie d’histoire Numérique de l’Europe [Online], June 22, 2020. https://ehne.fr/en/encyclopedia/themes/gender-and-europe/educating-europeans/gender-and-vocational-education-in-europe-19th-20th-centuries.

[4] Laot, Françoise F. “La formation des traivailleuses (1950-1968): Une revendication du syndicalisme mondial? Contribution à une histoire dénationalisée de la formation des adultes.” Le mouvement social, no. 253 (April 2015): 65–87.

[5] Richards, “Labor’s Gendered Misstep.”

[6] ICFTU Additional Inventories, Inv. Ad1034, Folder 1979-1985, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam.

[7] Cobble, Dorothy Sue. (2021). For the Many: American Feminists and the Global Fight for Democratic Equality. Princeton, New Jersey: Princeton University Press, p. 317.

[8] The conference tackled topics such as “the role of women in the struggle for peace in a democratic society, the needs of women workers in industrialized countries, the problems confronting them in developing countries, the coordination of trade union action in favor of women workers, and international solidarity.” International Labor 4, no. 3 (May-June 1963), p. 14.

[9] International Labor 5, no. 1 (Jan-Feb 1964), p. 19.

[10] Türk-İş/ICFTU Seminar on the Problems of Women Workers, 4-8 June 1979, Çeşme-İzmir. Ankara: Türk-İş Publications No. 126, p. 63.

[11] Türk-İş/ICFTU Seminar on the Problems of Women Workers.

[12] Reflecting the report from the Çeşme seminar, the Bureau defined its aim as follows: “the active participation of women in trade unions, enabling women’s use of their union and labour rights effectively, developing solutions to (women’s) problems from below, and providing women with necessary education in the fields of organization, communication, and health.” Türk-İş Dergisi, no. 149 (August 1981), p. 17.

[13] Cobble, For the Many, p. 381.

[14] Boris, Eileen. (2019). Making the Woman Worker: Precarious Labor and the Fight for Global Standards, 1919-2019. New York: Oxford University Press; Boris, Eileen, Dorothea Hoehtker, and Susan Zimmermann, eds. (2018). Women’s ILO: Transnational Networks, Global Labour Standards, and Gender Equity, 1919 to Present. Studies in Global Social History, Volume 32. Leiden; Boston: Brill; Cobble, For the Many; Laot, “La formation des traivailleuses.”

Illustrations:

- Photo from an educational seminar for women trade unionists at the Türk-İş Union College in Samsun, 1983. Source: Türk-İş Dergisi no. 171: p. 12.

- Marcelle Dehareng and Patronella Tegelaar with the Türk-İş president Seyfi Demirsoy. Source: Türk-İş Dergisi no. 60: p. 2.

- Book cover. Türk-İş/ICFTU Seminar on the Problems of Women Workers, 4-8 June 1979, Çeşme-İzmir. Ankara: Türk-İş Publications No. 126.