by Olga Gnydiuk

In 1948 at the session of the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) Executive Committee, Nina Popova, the only female delegate present at the meeting, ended her speech by expressing the hope that the number of women in the WFTU would soon increase:

“[…] the time would come when in the WFTU, the Executive Committee, and in the delegations of the CIO, the TUC, the French CGT. and in the organizations of yet other National Centers women would also be given suitable representation. By doing so, the WFTU would set an example of the way in which a practical solution should be found for the female question.”[1]

Eight years later the WFTU organized its first Conference on the Problems of Working Women. At the second conference dedicated to women’s issues in 1965, it was reported that 40% of the WFTU’s affiliated members were women.

The WFTU brought together communist and socialist trade unionists from Eastern Europe, several West European countries, as well as trade unionists from developing Asian and Latin American countries.[2] It was a male-led and male-dominated organization that nevertheless, from the very beginning, actively addressed the labour and social problems of women and underlined the importance of women’s participation in agenda-setting, trade union organizing, and labour struggle.[3] The main WFTU’s periodical, “The World Trade Union”, published articles on the problems of working women in different countries from Western Europe, North America, and the Global South. They also reported on the successes of women’s labour politics, and sometimes problems related to women’s work that stilled needed to be addressed, in state-socialist countries, such as Poland, Bulgaria, Romania, and the GDR. This blog post sketches the mechanism through which locally and nationally driven agendas and demands on women’s social and labour rights could possibly be transferred to the international levels of debate and agenda-setting. For this, it looks into the principles according to which the WFTU organized the conference on the working women issues and charters adopted at these conferences.

From 1956 onwards the WFTU regularly organized conferences on the problems of working women which were attended by delegates from the national trade unions of many countries and women’s organizations around the world. The conferences were also open for women activists not affiliated with the WFTU. The WFTU’s first World Women’s Conference took place in Budapest in 1956. The second one was organized in Bucharest in 1964, then followed by the conferences in Prague, in 1972, and Nicosia, in 1979. These international gatherings created the space for women trade unionists and functionaries to report on local labour issues, articulate demands, propositions and share their experiences.

The principles according to which the conferences were organized suggest that knowledge and practices circulated from the local to the international level. Pre-conference preparation pushed the national and local trade unions and women’s committees to arrange factory, local or national meetings, organize the exchange of workers delegations and correspondence. For example, to prepare for the conference in Nicosia, the WFTU supported national trade unions in organizing local and regional seminars and conferences for women activists in Budapest, Dakar, and Panama.[4] Such activities aimed at collecting information about women workers’ problems and concerns specific for each region and preparing the conference agendas and propositions that would help to solve the problems that would be addressed. As a next step, the reports summarizing women’s issues deemed relevant at the local and the national level would be presented and discussed at the upcoming WFTU conference. However, future research will help us to clarify the impact of these local and national preparatory activities on the agenda-setting for and the resolution-making at the WFTU’s conferences on the issues that concern working women.

In the conference, the delegates put forward the resolutions, memorandums, and charters on working women’s rights, which were addressed to the key international labour organizations such as the ILO. For instance, in 1964, the participants of the WFTU’s Conference on the Problem of Working Women in Bucharest adopted the Charter of Economic and Social Rights of Working Women. The Charter summarized the main demands and politics on women’s work “of women in all occupations in town and countryside, including women on outwork, and based on the given conditions in every country”.[5] It included demands related to the rights to work, equal remuneration, abolition of all kinds of discrimination, women’s access to technical vocational training, working hours, social security, protection of women and children, and finally, guarantees for women’s access to trade unions as well as the introduction of trade union education for women so as “to convince them in ever-growing numbers of the necessity to fight and organize”.[6] Louis Saillant, the general secretary of the WFTU, believed the Charter would “for a long time be the best means of action and especially an excellent program of social achievements” concerning policies on working women. “The Charter will assume an important place on our activities to advance with greater clarity towards the future we foresee for working women in general and for working mothers in particular”, he said.[7]

Participants to the following conferences on the problems of working women in 1972 and 1979 adopted similar documents under the new title “Charter on Economic, Social, Cultural and Trade Union Rights of Working Women”. In the Charter adopted at the conference in Nicosia in 1979 the delegates updated and extended the list of demands and agendas compared to the 1972 or 1964 Charters. In their opinion, this was necessary to reflect the transformations in the world of working women. Particularly, the 1979 Charter included a longer section concerning demands in the sphere of women’s reproductive rights, family policy, maternity and family allowances, working rights for pregnant women and “working mothers”, as well as a section on public preschool educational institutions.[8]

The Charters on women’s rights were the main agenda-setting documents of the WFTU’s women activists. They cast in a concise form the agendas and demands with reference to which WFTU trade unionists aimed to contribute to and participate in the transnational agenda-setting regarding the politics of women’s work in international key organizations such as the ILO. The WFTU women activists addressed the 1979 Charter to the ILO as a program for action and urged it to integrate WFTU principles into the ILO’s programs for action, including its international instruments. At the same time, the Charter was to serve as a “common platform” that the national and local trade unions could rely on and should refer to when developing their own agendas and engaging in their own struggles for the improvement of the working and living conditions of women.[9]

In post-1945 Europe, the WFTU was the main mixed-sex trade union international in the frame of which women activists from Eastern Europe and beyond worked together, discussed, and promoted demands on women’s social and labour rights. The principles according to which the WFTU organized the conferences with women activists around the world give the idea of how the WFTU became an important international platform on which women trade unionists and functionaries from various countries organized, established networks, raised issues, took action, and could contribute towards shaping the policy documents and agendas of the WFTU regarding the problems of working women. As WFTU representatives and delegates they could enter the web of other international organizations such as the ILO, the UN, and its agencies and commissions, working tirelessly for the inclusion of their own demands and agendas. At the same time, affiliation with the WFTU provided them with additional resources and opportunities to organize and exert influence on the politics of women’s work locally. The upcoming research of the ZARAH team will shed more light in this regard. Detailed exploration of the role of WFTU’s documents such as the Charter on Economic, Social, Cultural, and Trade Union Rights of Working Women in these broader international contexts, and the settings in which they were drafted, circulated, and implemented will help us to foreground successes and failures of women activists’ and functionaries’ internationalism.

[1] Dragomira Ganzalova, “Druzhba i Solidarnost’ v Bor’be. [Friendship and Solidarity in Struggle],” Vsemirnoe Profsoiuznoe Dvizhenie [World Trade Union Movement], no. 12 (December 1979): 3.

[2] World Federation of Trade Unions, Working Women Shape Their Future. 2nd International Trade Union Conference on the Problems of Working Women (Prague: Práce, 1964), 106.

[3] World Federation of Trade Unions, 105–8.

[4] World Federation of Trade Unions, 20.

[5] “Khartiia ekonomicheskih, sotsyal’nyh, kul’turnyh i profsoiuznyh prav trudiaschihsia zhenschin [Charters on economic, social, cultural and trade union rights of working women],” Vsemirnoe profsoiuznoe dvizhenie [World Trade Union Movement], no. 12 (December 1979): 7–11.

[6] Ganzalova, “Druzhba i Solidarnost’ v Bor’be. [Friendship and Solidarity in Struggle].”

[7] “WFTU Session of the Executive Committee, Rome, 5th-10th May, 1948,”, 99, Box 75-82. Folder 75, International Institute of Social History, Amsterdam, Netherlands. CIO – the American Congress of Industrial Organizations, TUC – the British Trade Union Congress, CGT – the French General Confederation of Labour (Confédération Générale du Travail).

[8] The WFTU came into existence in 1945. In 1949 the British TUC, American CIO and the American Federation of Labour (AFL) left the WFTU to establish a new international, the ICFTU, that brought together the trade unions not affiliated with the communist-led WFTU.

[9] Women’s participation in male-dominated labour and trade union organizations has increasingly become the focus of recent studies, see for example: Susan Zimmermann, Frauenpolitik Und Männergewerkschaft Internationale Geschlechterpolitik, IGB-Gewerkschafterinnen Und Die Arbeiter- Und Frauenbewegungen Der Zwischenkriegszeit (Löcker, 2021); Yevette Richards, “Transnational Links and Constraints: Women’s Work, the ILO and the ICFTU in Africa, 1950s-1980s,” in Women’s ILO: Transnational Networks, Global Labour Standards and Gender Equity, 1919 to Present, ed. Eileen Boris, Susan Zimmermann, and Dorothea Hoehtker, Studies in Global Social History 32 (Leiden: Brill, 2018), 149–75; Dorothy Sue Cobble, “International Women’s Trade Unionism and Education,” International Labor and Working-Class History 90, no. Fall (2016): 153–63, https://doi.org/10.1017/S0147547916000089. However, the work of women within the WFTU remains on the margins of research dedicated to labour activism, internationalism or women’s history. Individual stories about the women activists and functionaries from Eastern Europe in the WFTU and their international career paths are yet to be written.

Illustrations:

- Back cover of the WFTU’s brochure “Working Women Shape Their Future. International Trade Union Conference on the Problems of Working Women” Women and Social Movements, International (Prague: Práce, 1964).

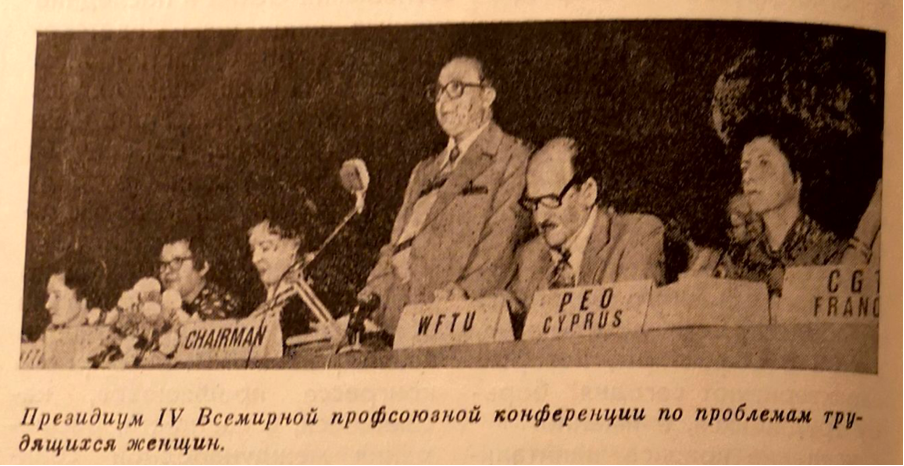

- “Presidium of the IV International Trade Union Conference on the Problems of Working Women.” Taken from: Dragomira Ganzalova, “Druzhba i Solidarnost’ v Bor’be. [Friendship and Solidarity in Struggle],” Vsemirnoe Profsoiuznoe Dvizhenie [World Trade Union Movement], no. 12 (December 1979): 2.

- A photo depicting delegates of the IV International Trade Union Conference on the Problems of Working Women. Taken from: “Zhenschiny v bor’be za luchshee buduschee [Women in Struggle for the Better Futur],” Vsemirnoe Profsoiuznoe Dvizhenie [World Trade Union Movement], no. 12 (December 1979): 5.